All the paintings are a result of crisis…

Frank Auerbach: A Compendium

(Compendium)

Frank Auerbach leads a short list of artists who dislike giving interviews, a dislike he wrote unreservedly about in a letter to his son, the filmmaker Jake Auerbach, just prior to the filming of To the Studios — a film that rightly places biography and backstory in service to the paintings Auerbach has been making for over sixty years. (Released in 2001, the film still feels fresh. Stream it here. You won’t be disappointed.)

The letter:

Dear Jake!!

A very quick, scribbly and incoherent letter to you and Hannah. Some of the things you said about the possible film last night made me uneasy. Hannah wrote me a letter, many years ago, asking me to appear on a program designed to demystify painting. I refused, of course. The thing is, painting is mysterious and I don’t want it demystified. It’s no good presenting artists as approachable blokes who happen to paint, although some may have the coolness and the grace to lend themselves to this. And in this case, you would be dealing with someone who is prepared to answer questions and to explain, but who is not prepared to lend himself to performing in a film, as though he wanted to contact the general public. If I have ever thought about contacting anybody, it is the misfit in the back room who rejects the general public and television films. I think that Hannah should know what kind of beast she is dealing with, the beast in a burrow that does not wish to be invaded. Of course I don’t mind and wouldn’t object to anything that other people say, but I think Hannah should interview me before making films and plans.

We compiled these quotes by Frank Auerbach (below) — and by others who have written about him — to do just that: answer a few questions arising from his work. For more on Frank Auerbach in his own words, begin with our citation of his July 2015 conversation with Tim Marlow at the Royal Academy in London. We hope you’ll find the side-notes helpful. And to be clear, an excerpt is precisely what that feature is — a fragment, and some context. We hope it will steer you back to the original text — or in this case, the original audio. As with each of our citations, we present it for the purpose of criticism, research or comment only.

I have never been particularly happy looking at my own pictures and have always found myself reluctant to talk about them… . I really don’t want to think about what affect—what I do—has on other people and I don’t feel happy with the idea of being interviewed.

The intensity of life with somebody and the sense of its passing has its own pathos and poignancy. There was a sense of futility about it and I just wanted to pin something down that would defy time so it wouldn’t all just go off into thin air. This act of portraiture, pinning down something before it disappears, seems to be the point of painting. Our lives run through our fingers like sand, we rarely have the sense of being able to control them, yet a painting by a good painter, say by Manet, Hogarth or Velázquez represents a moment of grasp and control of man over his experience. It makes life more bearable.

I thought often that I had finished it only to become dissatisfied, and remember as a vivid event the afternoon on which I finally and definitely completed it. I thought I had finished it on the day prior to that afternoon. The painting was then almost black. I suddenly realised that I could work on it further. I turned the picture upside down and completed it the next day.

The artist’s remark that he had turned Primrose Hill upside down refers to his procedure of working on the imagery from all four sides of the picture. (He rests the picture on each of its edges). He said that he did this to ensure that the images and marks were correctly related to each other in every direction. He confirmed that painting in this way approximated to carving an object in sculpture and produced the following analogy:

One does not make a machine without turning it upside down to see whether it is properly constructed underneath.

I also want it to be an extraordinary image. I mean, I got a photograph this morning through the post of something that I finished about two months ago — and I find it very valuable because … I don’t brood over things, I don’t look at things, I like to ship them out as quickly as possible — and this looked to me a bit fierce, a bit wild, a bit strange as an image, and all these things that one does to lead up to it are — finally — so that there should be an image on the canvas, in the frame, that has its own life and its own vitality, and I hope it wakes one up and disturbs one.

I feel that I’m going further when I paint same the person again. I feel as though — there is no such thing as a definitive encapsulation of person, and if you’ve got one, you feel that something else has escaped one…you try for another… . It isn’t a conscious process–I don’t think I’m going to do this about that person—it simply happens. Sometimes I’m more ruthless, sometimes I’m more observant, sometimes more determined…

They [his sitters] are all people I respect and like. And…their mood certainly does affect me. You know, it’s not an easy process. Backache comes into it and being tired comes into it. And I’m extraordinarily grateful. And people go through different stages in their life. And all these things have their effect on me. And I behave differently with different people. Some talk more, or I talk more, and some less— It just creates a different atmosphere and different way of behavior. I can’t pin it down further than that. But I feel that I’m going further when I paint the same person again. I feel as though there’s no such thing as a definitive encapsulation of a person if you’ve got one, you feel that something else has escaped one, you try for another…

I find it very, very difficult to imagine being in a room by myself and looking at a wall and thinking, What art shall I do next? Because I want it to be something that stands up for itself and that works by its own rules and that even if you saw it upside-down or half-way across the world, it would still have a vitality — which is finally, I suppose, a sort of subtext, or inner vitality.

But for me that arises entirely from my physical experience, my place in the world. [It’s not what I hoped to do, but I realized that unless]… Sickert says somewhere, slightingly, of something, That it isn’t exactly like a page torn from the book of life; and, actually, I’d like my pictures to feel as though they were a page torn from the book of life. And I have to say that 95% of the pictures I see on the walls seem concoctions to me.

Auerbach: All great paintings are classical in the sense that it’s complete in itself. “Concoction” I think means that works like a game of spillikins, or pattern making – without any component of the poison, the strangeness, the oddity, that justifies the existence of the picture … I was referring to the academic nude… If you pose a nude in what’s supposed to be a classical pose and then tell people to paint it in a certain way, and they have no particular connection with it, the whole thing might appear to be a concoction. If you take triangle square and a straight line, and arrange them in what seems to you to be some harmonious way, you know, it’s a sort of recipe without introduction of the bit of poison, the bit of strangeness, the bit of raw life that justifies the existence of a work of art.

Audience Question: And that strangeness can never be pre-conceived, do you think? Or does it have to emerge through the process —

Auerbach: No, I don’t think it can. I think that’s the perl in the oyster. I think that’s the thing that irritates the picture into being.

Tim Marlow: you would not deny that, being a painter in London, in the period that you’ve been in London, and having the connections with various artist that you had, has had a profound impact on who you are and what you are…

Auerbach: Absolutely. I wouldn’t be anything like what I am now. That’s absolutely true.

Tim Marlow: And you feel part of the universal tradition, or at least a Western tradition art that goes a long way back as well.

Auerbach: Yeah … I mean, it sounds really soppy. When I’m in the studio — and I’m sure this is true of everybody, particularly, perhaps, of my generation… Giorgione came to mind the yesterday — he might’ve been in the room with me… this is what immortality consists of. Some aspect of these people still have life for the living and working now. [Painting] is a human construct. It’s formed by everybody who’s done it. And when you’re doing it any way that means anything at all, you’re surrounded by the example of all of the immensely complicated implications of everybody who has worked before you.

The problem of painting is to see a unity within a multiplicity of pieces of evidence and the very slightest change of light, the very slightest, tiniest hairs-breadth inflection of the form creates a totally different visual synthesis, I actually more or less start again every time the model rests and gets up again, but my mind has travelled along certain paths and tried out certain possibilities and created certain hopes, so that I somehow digest some of the possibilities. When the conclusion occurs and I feel I’ve been lucky enough to find some sort of whole for this overwhelming and unmanageable heap of sensations and impressions, I think that the previous attempts have contributed.

…as soon as I become consciously aware of what the paint is doing my involvement with the painting is weakened. Paint is at its most eloquent when it is a by-product of some corporeal, spatial, developing imaginative concept, a creative identification with the subject.

…that there was an area of experience — the haptic, the tangible, what you feel when you touch somebody next to you in the dark – that hadn’t perhaps been recorded in painting before

I try to paint the whole picture all the time. Even a beautifully painted section is not of the slightest use to me unless everything is interdependent and lives within the same flow…

I want everything in the painting to work, that is, every force, every plane, every direction to relate to every other direction in the painting — so there’s no paradiddle or blot somewhere. I feel very strongly that if a painting is going to work, it has to work before you have a chance to read it. Great Rembrandts shake you. There is a tension between unity and difference; one great wave or wind holding it all together as one. A [good] painting concentrates the experience of being.

The closer one is to something, the more likely it is to be beautiful… . The whole business of painting is very much to do with forgetting oneself and being able to act instinctively. I find myself simply more engaged when I know the people. They get older and change; there is something touching about that, about recording something that’s getting on…

Likeness is a very complicated business indeed… . If something looks like a painting it does not look like an experience; if something looks like a portrait it doesn’t really look like a person.

Auerbach’s painting is not an image of an image, and not really an image at all, but an investing of awkwardly viscous oil paint with an accretion of subjective perceptions.

An abiding contradiction between a rigorously empirical intention and a language of abstract notations characterizes the work of the group of painters—particularly Auerbach, Leon Kossoff and Francis Bacon — who emerged in 1950s London, pitching a dissenting representational idiom at the modernist mainstream, even as their work assimilated some of the contemporaneous discoveries of Pollock and de Kooning. Auerbach’s version of this approach is a strenuous but unself-conscious gesturalism, the consequence of a mind and hand consummately absorbed in arriving at an unpremeditated solution that equates to the painting’s subject without illustrating it. Such flights of fancy do not detract from the hair’s-breadth accuracy of the draftsmanship. No attention is free to intentionally make “Auerbach marks.” The mire of postmodern self-reflexivity is circumvented, as the marks, assimilated by the order they comprise, fuse into often outlandish, but always precise, metaphors for the reality they capture.

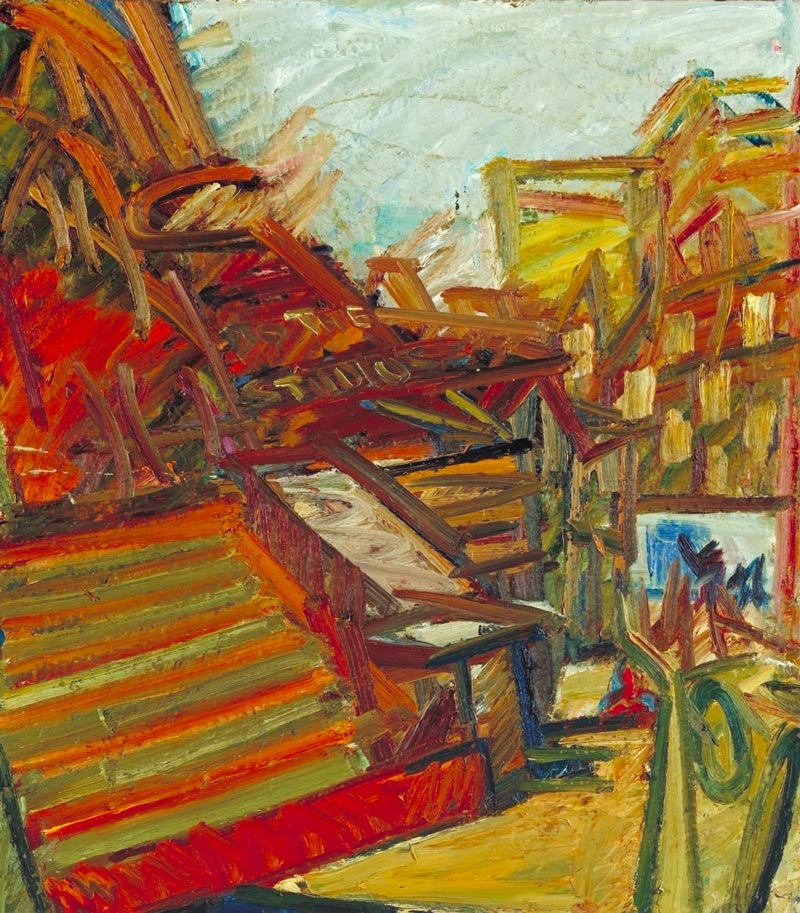

There was a precedent for Auerbach’s use of raw and rough subject matter — muddle, rubble and building equipment — in the work of an English painter of the past he greatly reveres: John Constable. ‘Constable’s subject-matter was at least as shocking as Gilbert and George’s is: barges, rotting stumps, things that hadn’t been recorded. This was a person blatantly shoving rubbish into our faces and making grand, Michelangelo-esque compositions of it.’

I really wasn’t deflected at all by changes in fashion. It never, never occurred to me. I never had that feeling of everything collapsing because I started from a very low point, and gradually things got better until now. I’ve done miles better in my 70s than ever before.

More unexpectedly, one of the formal triggers for Auerbach’s building sites was that 18th-century master of the landscape with ruins, Piranesi. ‘I remember going to David Bomberg’s class at the Borough Polytechnic, and him showing me — as much as to say how can I kick this student who doesn’t understand what’s going on? — Carceri, the Prisons. At that moment I remember suddenly seeing that there was a real excitement in the wordless and subject-less tension of the structure in space.’

I actually had been painting building sites since I was about 17. You know how when one is young, everything has a very strong effect and one remembers much more of those years than one does of any other? I’m speaking here for a young man who no longer exists and of whom I’m a rather distant representative. I think there may be some feeling of that turmoil and freedom in those pictures that there was in London after the war. There was a curious feeling of liberty about because everybody who was living there had escaped death in some way. It was sexy in a way, this semi-destroyed London. There was a scavenging feeling of living in a ruined town.

In sum, Auerbach found himself admiring in de Kooning what he admired in Soutine — the sort of draughtsmanship which is deeply painted, bathes shapes in air and carries the eye around the back of the form, rather than leaving it with the contours and colour of a flat patch. If any American artist of the 50s seemed to Auerbach to have matched the terms of Bomberg’s ‘spirit in the mass’, that person was de Kooning. The example of Abstract Expressionist gesture did not wreak a sudden change in Auerbach’s work, as it did in other English painters… . Instead it was slowly and cautiously absorbed, slowed down by the thickness of Auerbach’s surface, which it energized in terms of vectors pushed through the paint — directional brushstrokes which wiped aside the clutter of pentimenti under the paint-skin. The first work in which this became clear was Shell Building Site From the Thames, 1959, a view down into the deep cut of the excavation for the skyscraper.

1Frank Auerbach quoted in Alistair Hicks, “Frank Auerbach, Painter in Crisis,” The Spectator, London, 30 May 1986 : 37. (Retrieved 21 August 2016.)

2To the Studios, Hannah Rothschild (Writer/Director) and Jake Auerbach (Producer). London : Jake Auerbach Films Ltd. : 2001. Reprinted by kind permission of Jake Auerbach Films, Ltd., London.