The Artist as Blind Seer: A New Perspective on de Chirico

A New Perspective on de Chirico

Brian George

All around me the international gang of modern painters slogged away stupidly in the midst of their sterile formulas and arid systems. I alone, in my squalid studio in the rue Campagne-Premiere, began to discern the first ghosts of a more complete, more profound and more complicated art, an art which was — to use a word which I am afraid will give a French critic an attack of diarrhea — more metaphysical. New lands appeared on the horizon. The huge zinc colored glove, with its terrible golden fingernails, swinging over the shop door in the sad wind blowing on city afternoons, revealed to me, with its index finger pointing down at the flagstones of the pavement, the hidden signs of a new melancholy — de Chirico, 19181

Giorgio de Chirico, who was born in 1888 and died in 1978, is an artist who is widely, but not deeply, known. Perhaps the most important immediate predecessor to the Surrealists, who adopted and then abandoned him, he exerted a direct influence on Max Ernst, Salvador Dali and Rene Magritte, among others. Try as they might, the Surrealists could never quite manage to escape from the long arm of his shadow, and it is certainly odd that we must thank the artist’s detractors for also serving as his most energetic advocates. It was they who first crowned him as a hero of High Modernism. It is equally odd that he was accused of pale self-imitation by the very group that had appropriated his techniques. In 1926, a crossed-out reproduction of de Chirico’s Orestes and Electra — painted three years earlier — was printed in “La Revolution Surrealiste,” as an illustration for Breton’s essay “Le Surréalisme et la Peinture.” The group referred to him as a “dead painter,” and in 1928 Breton declared, “He no longer has the slightest idea of what he is doing. What greater folly than that of this man, lost now among the besiegers of the city he had built and rendered impregnable.”2 Given this contempt, it is certainly odd then that, in 1929, the group greeted the publication of Hebdomeros, de Chirico’s semi-autobiographical dream novel, with near-unanimous and enthusiastic praise. “Et quid amabo nisi quod aenigma est?” “And what shall I love if not the enigma?” reads the inscription on the window frame of a 1911 self-portrait. Both to others and himself, at no time was the artist other than problematic. This was no less true in 1929 than it was in 1911. No catastrophe had snuffed out the metaphysical flame. No anxiety had shut down his ability to reinterpret the strange geometry of the labyrinth, or to breathe the air of a city that had disappeared off the coast. Throughout his life, he had no choice but to follow in the footsteps of his daemon, as I do also. The thread in the artist’s hand led only to the next act of subversion, and then to the one after that, and then so on to the next. Trusting in the wheel of the Eternal Return, he was obstinate in his belief that he had not died at the end of the First World War. Many have preferred to replace the real artist with a simulacrum.

In any event, there are few histories of modern art that do not have at least a small section on de Chirico. His images of deserted squares and empty headed manikins are iconic, in the manner of Dali’s soft watches, or Picasso’s through-the-looking-glass faces. Having inhabited a corner of our collective consciousness for over 90 years, the work is in some way recognizable even to those who have no idea of who the artist was. It is possible, however, that its significance has never been fully assimilated or explored.

You could, until recently, search long and hard for an art historian with any original insight into the world that de Chirico created. Most have been content to recycle the comments of other art historians, who in turn have paraphrased — with a footnote here or an anecdote there — a handful of the artist’s own pronouncements. Comments from detractors such as Andre Breton — who first set the Before Genius (or B.G.) and After Genius (or A.G.) dates — must of course be introduced, but these do not help us to more rigorously probe the symbolic language in question; they only taint our attitude towards it, and thus prompt us to see potential virtues as deep flaws. Breton was the first of the many friends turned foe. In a rage he threw at the artist’s later work the pronouncement of anathema, an act that clouds the minds of critics to this day. Such betrayals only confirmed the artist’s perhaps megalomaniacal but oddly accurate sense of himself as someone chosen by the Fates, as a solitary seer with the mark of the infinite on his forehead.

There is little to be gained by a recitation of the common wisdom, as exemplified by critics such as James Thrall Soby, Robert Hughes, and William Rubin, in which the early work is praised and the later work condemned, or by the throwing away of any parts of the puzzle that do not conform to our image. This is usually called cheating. Critics like to tell stories, in which each style grows logically from the style that preceded it, and the development of an artist moves in a straight line. They do not like to be forced to figure out how an artist can be simultaneously a genius and a fool, a revolutionary and a conservative, a visionary and something of a conman. Certain patterns can be grasped only by reaching through a multitude of dimensions. To see at all, we must trust that they cohere. Each term in a relationship must be taken in at once, for contradictions can serve to illuminate the whole. However big their heads, we should not assume that the judgment of a hundred or so critics is superior to that of one artist, even if that artist is not 100 percent conscious. Time will tell, as will the sea, from which the baby thrown out with the bathwater is scheduled to one day return. Heraclitus says, “Character is fate.” James Hillman, in “The Soul’s Code,” expands on this idea. He writes, “Necessity’s implacable smile says that whatever choice you make is exactly the one required by Necessity. It could not be otherwise.”3 The beginning of a closed curve is not different from its end, or telos, the goal of the magnum opus that is peculiar to each person. The end serves as a strange attractor, able to bend the laws of nature, like a network of knots, around itself. Thus the image of one’s character encompasses all later apparent detours and distortions. One’s weaknesses are just a mirror-image of one’s strengths. If de Chirico is one of the most original artists of the 20th Century, or at least of its second decade, then he is also one of the most difficult, or even maddening, to try to place.

It is only in retrospect that the pattern as once imagined by the daemon can be viewed, that the whole snaps into focus. For years critics have competed to display their almost complete indifference to this pattern. One de Chirico is good. The other is bad. Supporters of the artist’s early work would instead be better served by attempting to imitate its example, in the posing of new questions about the nature of reality, and in refusing to accept the most solid of illusions at face value.

At once strange and familiar, as though deliberately crafted to illustrate Freud’s concept of the uncanny, the work has, Paul Valery argues, “become part of the permanent furniture of our mind.” And therein lays the challenge. It appears as though we have seen this all before. There is an odd circularity about the whole business of the commodification of a set of symbols — a circularity prefigured in the work itself, whose logic is that of a pregnant but unmoving dream. It is only over the past 15 years or so that the situation has begun to change.

A few recent critics have begun to wrestle with the work produced from 1920-1978, a period that encompasses two thirds of the artist’s life. Unlike the more famous work, produced from 1910-1920, this self-contradictory oeuvre has seldom been treated with complete seriousness. It is in this later work that de Chirico attempts to integrate the energies of the prophetic vision that first picked him up and carried him off. There is certainly a lessening of the stark intensity that first characterized this confrontation with the infinite. (Medusa and all of her sisters wept!) It is possible that the artist might have died of metaphysical exposure had he not replaced the incantations of the magus with the slight-of-hand of the stage magician, had he not crafted a method to insure the continuity of the human vehicle.

There is one question that we must always ask about de Chirico: Who or what is speaking or acting on any given occasion? For he is not one self-contained being.

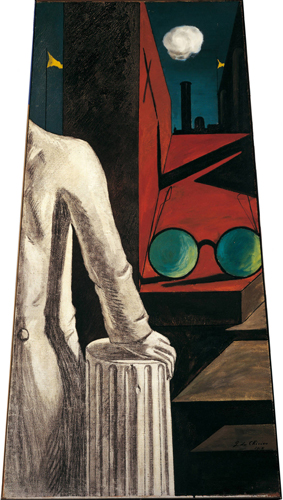

At each turn, images of doubleness abound. There is simple doubleness and complex doubleness. There is the doubleness of the ideal distorted by the methods of reproduction. There is the doubleness of the object and its shadow. There is the doubleness that treats the artist like a child in his quest for occult potency. There is the doubleness of vision and the sunglasses of the seer. There is the doubleness of the light showing through the black fog of each tunnel that the artist turns in a labyrinth. There is the doubleness of transformation and the threat of actual death.

In The Lassitude of the Infinite, as in many other paintings from the period of 1910-1920, long shadows project from two tiny figures at the far end of a vast piazza, at an angle to the reclining stone Ariadne in the foreground, gigantic in comparison. The two figures stand or walk, in silence or in conversation, as Ariadne, wronged by Theseus, broods in melancholy transport on her plinth. Trailing a long plume of smoke, the locomotive of Theseus steams toward Athens in the background, behind a low brick wall that separates the piazza from the ocean. In paintings from this period, there is almost always space between these two archetypal figures. They seldom touch, but instead display the formality of diplomats. So thinly has the artist painted them that they appear to be two spirits who have materialized from the aether, or two shades who have accidentally wandered from the Underworld. Space consumes them. They are only just barely present in this dimension of existence.

In the later works, however, and especially in the long “Piazza d’Italia” series, the two figures are usually pushed much further toward the foreground. Wearing suits, they have turned their faces toward the viewer, and are far less spectral and more three dimensional. Anxiety — both that of the artist and that of the Dioscuri — is now more or less under control. The mood of wrenching loss has evaporated. Props in the background have been mass-produced, as minute variation plays the part of the visionary seizure. The two figures have walked and stood on this piazza a great many times before, and yet they are not where they are, or where they believe themselves to be; how odd it is then that every detail looks the same. By the reproduction of the fixed form of a memory, the artist has attempted to partially literalize its content. In this way, he both invokes and regulates the power of the symbols that had once been broadcast from an alternate reality. All of these things are significant, but the crucial change is this: in almost all of these later compositions, the two figures are portrayed in the act of shaking hands. Perhaps they are off to the Caffe Greco for a few cups of espresso and some pastry. A gesture seals the new understanding between the human and the infinite. For the moment, a truce.

It is certainly true, the opinions of dead friends and/or enemies aside, and whatever we might think about the period from 1920-1978, that the earlier work does reward the most intense of engagements. All themes are present in an embryonic form. The mature de Chirico approaches it like we do — as the product of a dangerous god. It is as though this work were a weapon aimed at one’s unconscious by the Other. Enlightenment is to follow upon death. In this world, we make do with a course on Modern Art Appreciation.

“The Avant Garde moves, while Alexandrianism stands still,”4 writes Clement Greenberg, the Torquemada of High Modernism. But the archaic can also move. Emily Braun, in her 1995 essay “A New View of de Chirico,” contends that de Chirico “adopted Nietzsche’s perception of modernity as the age of comparison, wherein all styles, civilizations, morals, and habits can be seen side by side, and are available to the common man and aristocrat alike.” 5 The city beloved by de Chirico is a stage set, no more and no less, in which each term of a contradiction can be seen as provisionally real. If there is no true conflict between the early and the late, it may be possible to postpone one’s choice between them, or even to sidestep the opposition altogether, in order to investigate the strategic threat posed by the silent but still dangerous god. As we note that each thing in this city has a predetermined place, that a bond exists between apparently disconnected objects, we might imagine that lines drawn between the stars have somehow converged again on the Earth. We may note too that, in a joint venture with the Muse of Astrophysics, the double’s hand maps vertical time onto horizontal space, leaving only a few cues that there are no keys for the locks. “The same anew,” writes James Joyce. There is no lack of time or mutability on the wheel of the Eternal Return. All that is solid melts into the air. All that is liminal becomes concertized.

+

Is there something in the nature of the work itself that frustrates all articulate interpretation? I would argue that there is. The images do confront us with inscrutable demands. Is the omnipresent sense of paradox an obstacle or a key to the works’ power, its potential to obsess and fascinate? I will return to these issues in a moment. First, let me speak to how a system of obscure signs can activate the intuition and enter directly into the bloodstream of the unsuspecting viewer.

At the age of 16 I discovered the work of de Chirico — with a shock. It was not like leafing through the work of other artists, Van Gogh or Gauguin, for example, who had earlier transfixed me. It was instead more like discovering a new world, or being altered by a drug, which had the power to rearrange my entire way of seeing. I was possessed by an experience that was not my own. On the edge of sleep, all of the objects in my room would transform themselves into objects painted by de Chirico, as the breath of the artist leaked in through the windows. My emotions were those of someone who had lived through the First World War. The present moment was as tangled as the rigging of the Sargasso. As in a previous world, the deaths of millions struck us as a pointless aesthetic game, whose absurdity only the deepest insight could transmute. The Infinite had left its thumbprint on our foreheads. I could not do much of anything, and yet, like the young de Chirico, I was convinced that I was a genius. The light by which I saw was not thrown by my lamp. Should my mother pause at the door, she would instantly be changed into a manikin. My heart would pound. I would jump out of bed, ready, almost, to scream. Dead gods would hold a convention on my tongue. The room would spin. Whatever your interpretation, and against appearances, I was very clear and sober, and would watch in horrified fascination as my childhood grew strange.

+

My head spins, and I shake to remember how those ancient ghosts had once descended on my bedroom. As the years have drifted past, de Chirico has continued to challenge me at each turn of the spiral, at each new stage of creative growth — stages that he has sometimes helped to catalyze. “Trust death,” he says. “It is the Archemedian fulcrum, the point of crossing, a platform for the lever of the metaphysical double.” Chance liberates the mute connection between objects, thus articulating the agenda of a multidimensional labyrinth. Beyond good or evil, the One as imagined by Parmenides coheres, as a sphere that cannot be broken. The desire of each individual object is obscure. A gulf separates the One and the Two.

Hieroglyphs wear as camouflage the whole length and breadth of history. A rubber glove is looking for its hand. The past stores energy for future use, even when no action is apparent in the present, beyond that of the wind. Pain rises like a seismic shock wave through the feet, as a not yet declared war provokes an intestinal revolution. The auras expanding around each object speak of a great work against nature, of a cold sun, pulsing without love. The artist instructs me to greet the fears of the living with indifference. Always, it is time to go.

+

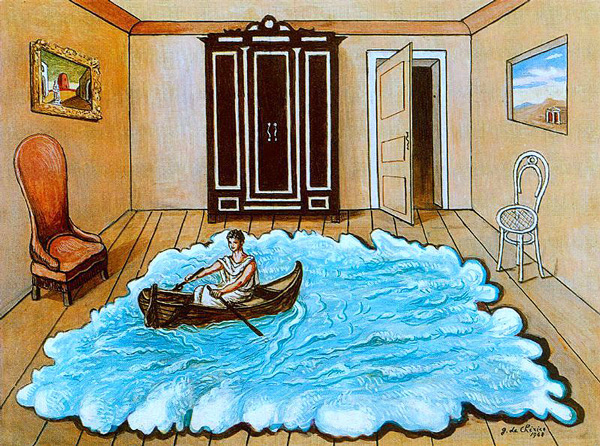

In de Chirico’s work, something is always just about to happen. Behind a wall a ship is waiting to depart. Only the sail is visible. We infer that the ship, like the ocean that rocks it back and forth, is there. A locomotive whistles in the distance, appearing to speed. A puff of smoke from its stack is frozen in mid-air. There are towers and arcades. Freud might say that these were sexual symbols. There are the instruments of an architect, cannon balls next to a cannon, a spool of Ariadne’s thread that has been abandoned by a factory, the map of a distant coast, a clock whose hands have frozen at six minutes before three, a big bunch of bananas, a plaster of Paris foot and children’s toys. Signs point in opposite directions, leading us, after great exertions, back to where we started.

Perspectives collide. There are multiple vanishing points. Of the six to be found in “The Melancholy of Departure,” for example, not even one is correct. Every element looks as clear as one of the principles of Newton. It is only the result that is contradictory. The lines are exact, but the space does not add up. The clock on the brick tower tells us that it is 25 minutes past one. In this as in many other pictures, the lines of perspective point towards the depths of an infinite sky. The horizon intoxicates, yet it is oddly difficult to move from our position in the foreground. And if, in a few hours, we find that the scene that we are looking at has changed, then it may not be at all clear how we have travelled from one spot to another.

In revenge for hubris transformed by Medusa into stone, the statue of a patriarch still dominates the square. He can only dream of sleep. He has not halted his investigations, and stares one-pointedly in our direction as we pass. There is, no doubt, a spirit trapped inside this statue, or a god, who would appear to expect some service on our part — at some point soon to be specified — which might eventually lead to its release. It sometimes seems that the dead change places with the living, without either knowing that a change has taken place. Shadows become more important than the objects that project them. The unseen is more powerful than the seen. There is no way through or out of the beyond. Let us say that we ask a question, a pregnant one; it is some stranger who hears the almost irrelevant answer. Like a radio signal, close at hand but inaudible to those not tuned to the station, there is also a larger presence that inhabits the somewhat greenish atmosphere, where to his own ends he manipulates events. By what antediluvian technology does this guardian curve time and space, so that, at the end of a long voyage, we find ourselves in the same autumnal square, facing the enigma, wrestling with a shadow that does not permit us to escape? The dream turns on itself. It has no beginning, and will have no end. Mark C. Taylor writes, “The origin of that which has no origin is the origin of the work of art.” 9 The exit from and entrance to the labyrinth are the same, but a figure eight is a more complex closed curve than a circle. It goes down to go up and up to go down. When the curve of the infinite intersects with the world, its movement is defined by a peculiar repetition; we have seen this curve before. It manifests. It finds its corresponding image, yet the second curve is not an exact reproduction of the first. Friction is produced, causing a spark to jump into the artist’s mind. The curves meet in a point that does not have a location.

+

Is there a reason that critics have not successfully deciphered the challenge posed by de Chirico? Again, I would argue that there is. De Chirico’s art not only presents us with an image of the enigma, it places itself directly in the viewer’s path to reproduce the experience of the enigma, as first internalized by the artist in 1911, in the shadow of a smokestack, on the eve of the First World War, in such a way that the enigma issues ultimatums to the viewer — its newest protégé and victim.

Each picture tells a story, of a kind, in which every grammatical element is obvious but the overall plot of the story is opaque, and becomes more not less so after intellectual scrutiny. It is as though we had left behind somewhere the greater part of our memory, and continuously scanned the environment for clues as to where we might have left it. Emotions remain strong. Sensations once associated with the occluded content can without warning grow dangerously intimate. Omnipotence returns — as a symptom. The catastrophe that created our amnesia can never be too directly questioned or approached. It must always be viewed out of the corner of one’s mind. Thomas Mical writes, “Within this circle, what is forgotten? That everything must return; the ‘possibility of ‘lightness’ is exiled outside the labyrinth, and also everything that would prevent eternal recurrence from seizing the self for ‘the first time.'” 11 For no good reason, a bored child will sometimes break his toys. The Aeon is also like this. We, the less than innocent onlookers, must pick up all of the pieces. Who knows but that our ignorance is a hoax? By the force of his will an artist must find the joy inside of terror.

Planets align. False harmony arranges them like a row of murdered gods. Smoke rises from the abstraction of the underwater holocaust. There were prodigies. There were methods of counting. There were perfect geometric models. There were towers of a truly absurd height. A buoy clangs, somewhere. Death transports the living to a predetermined climax. There is nothing left but a fragrance — a souvenir from history, to be examined on a star. The gift is acceptable to the attendants of Omphalos.

Quite suddenly, provoked perhaps by a shift in the constellations, or by the sight of a few toys, which make us sob, what we know of our small part in the story breaks through in a flash. A bird song rises from the now inanimate depths. The once beloved city opens like a book from which some unknown power has ripped all of the pages. What we know of our small part in the story breaks through in a flash — to just as quickly disappear. Our heads are hollow, as the head of every manikin should be hollow. The winds from interstellar space blow from one ear to the other, whistling with skewed harmonies, echoing, leaving us in doubt about just where our boundaries are. We are footnotes to the former versions of ourselves. We do not have mothers or fathers, but have been manufactured by a factory that has long since ceased to exist. Yet again, like the artist who in his solitude befriends us, we can sense that a new world has dawned, with its boom of guns, with its flourishing of flags and of manifestos. Our heads continue to be as hollow as they were, in the mode of emptiness that an archetype has modeled, as the laws of nature have determined that they must be in the future. And to think, that we had once been set before the public as a sign of double’s occult potency. It has seemed advisable to craft a method from our curse.

Like us, Egyptian embalmers had little use for the brain, and believed the heart to be the seat of true intelligence. It is said that absence makes the heart grow fonder. We can feel the magnetic action of the tides. We can smell salt in the air. There is an emptiness that is more articulate than the metaphors of Homer, than the laws of Hamnurabi. The good painter, also, should remove his eyes, in order to perceive the clockwork mechanism of the fates.

+

The energy trapped in the object is the record of our previous existence. Like a star sentenced to 12,000 years hard labor, the archaic spark desires to erupt out of unconsciousness, to return to the scene of the crime, to reenact the dance of its transgression. Black zigzags know what to do. Solid, almost painful to the touch, as if out of nowhere the energy now incarnates as a shadow. It is the psychopomp, who remembers how to navigate by scent. Blowing in the viewer’s ear, he points to the locomotive frozen in the labyrinth, with its puff of smoke that does not, for a century, move. Gilles Deleuze writes, “The form of repetition in the eternal return is the brutal form of the immediate.” 13 As our hunt for occult wealth intensifies, the eyes of the inanimate stare back at us. The object takes on a new and subversive life. There is a genie in the lamp. There is a ghost in the machine.

The suddenly unknown object can provoke as many flights of association as a cloud. Its lack of a fixed nature allows us to participate; we can dream of alternate worlds. Unlike a cloud, however, the object has a history, from which it is more difficult to escape than we believe. To dream is not an innocent amusement. There is a genius standing behind the genie of the lamp, who has visualized these phenomena a great many times before. If the dreamer wakes, his tongue then becomes a weapon. The music of a dream assaults the demiurgic spheres. Beyond them, in a reversal of the first act of creation, the incarnate watcher replaces his gross body with a double, without bothering to take off the body that he has. Taking some few objects with him, the magician conjures his body into the clear light of existence. It is said that this light is the light of the Ideal. Beauty lives there. Every action produces an equal and opposite reaction. Shadows lengthen beyond measure, monstrously, crossing seas and continents to arrive at the land of the never born.

Every 26,000 years the Dioscuri, who are the immortal twins, draw lots. The loser must set sail. The genius standing behind the powers of manifestation is the daemon, who is neither good nor bad. He is something else — a dangerous presence, a force beyond the contradictions that one’s intellect imposes.

It is the daemon who projects the sensation of foreknowing. We may experience this as déjà vu, but such an accident of vision points not only to the future, to a set of symbols that we half remember from a dream, to events that have not yet taken place. No, the experience is more complex and less linear than that. It is our small glimpse at the wheel of the great Platonic year, at the paradox of the Eternal Return. We stare in stupefaction at a city that has also, in a different place, existed, both physically and metaphysically, and in many close variations. The concept of the series in de Chirico can in this light be seen as the reenactment of a myth; it is an echo of the technology that once existed before the Deluge, a myth that no key can unlock. Time being what it is, the distant past may even now be present.

The disquieted muse mutters to herself. Again, there is a green glow in the sky, like that before a hurricane. Clouds hang like distended stomachs. In the statue’s prosthetic limbs, the sensations from a world war have not ever disappeared. Once a rising star among patriarchs, he cannot detect any progress in the construction of the stadium, or begin to figure out why the scaffolding has already been taken down. He is not as quick as he was. A layer of stone has now accreted on his armature. Fate’s victim, although conscious, is inanimate. Strength of will alone has empowered his nostalgia, as he goes in search of the great dream that exploded, of the wonder of the ideal, of the lands lost in a war against the alphabet of silence. North Asia crawls with obscene revolts. Average humans may one day deconstruct the black experiments that created them. The spell that made us stupid will be lifted, and a boy will laugh at the stone phallus of the Demiurge, which looks much like the statue’s own. At the stroke of midnight, toys will then riot through the laboratories of the Athens Polytechnic Institute.

+

The artist’s shadow has declared his independence from the wheel of the Eternal Return. He obeys no law, but instead appears in the period he chooses. He is not a projection of the needs of either the living or the dead. Taking the sun with him, like a weapon aimed at the ego, he can no longer be bothered to imitate every gesture of the pedestrian. It had been years since the metaphysical revolution had attempted to subvert the myth of progress. Since 1920, many towers had been built to equal that of Babel, though this time, much more durably, out of glass. The Bureau of Eugenic Purification had been closed — a fool’s errand in any case, as if anything could have affected the arc of our descent. Fascism was born again as evangelical Cubism. Biotechnology was on the march for the first time since the Deluge. Always, the enigma remains. The thread that binds an artist to his history. The reason for the gulf that separates the two hands of a clock.

De Chirico was sad. The 1972 New York Cultural Center retrospective, called “De Chirico by de Chirico,” had not provoked any radical new theories about or reassessment of his oeuvre, as a hieroglyphic dream had once led him to expect. He had done what he could. Mocked by his enemies, the knot people, grouped with reactionary critics like Sir Alfred Mummings, a dinosaur, and his only source of applause in one lecture on the Baroque, his obsessions a test of patience even for his friends, he would leave any unmet challenges for some starving artist in the future to resolve. Perhaps, already, the clockwork mechanism of the fates had arranged for their introduction, or would do so at the earliest convenience of the daemon. It was time, again, to set sail, but in a boat no longer seaworthy.

Death would untangle the huge knot that was life. Death, in its turn, was a different type of knot. In a small room hung with fishnets by the docks, the metaphysician brooded on the conundrum of the Eight, that perfect figure, which a prehistoric hand had once stamped on his forehead, like a curse. It was this action that had generated the topology of his pictures, those faithful reproductions of the nonexistent originals, which he had first seen in a vision from 1912. Or perhaps it could be said that even at that time, in a kind of reverse perspective, the complete works of de Chirico were already in existence, waiting only for the artist who would claim them, and for a bit of blood to reactivate their symbols.

Thought must so detach itself from all human fetters that all things then appear to it anew — as if lit for the first time by a brilliant star. — de Chirico, 1912 15

1 Giorgio de Chicico, “Zeusi l’esploratore,” Valori Plastici, Volume 1, Number 1, Rome, 1918, page 78

2 Andre Breton, Surrealism and Painting, New York, Harper and Row, 1972, page 69

3 James Hillman, The Soul’s Code, Random House, Inc., New York, 1996, page 210

4 Clement Greenberg, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch”, Partisan Review, 1939, page 38

5 Emily Braun, “A New View of de Chirico,” from De Chirico and America, Hunter College of the City of New York, Foundazione Giorgio E Isa De Chirico, Rome, Umberto Allemandi & C., Turin, 1996, pages 18

9 Marc C.Taylor, Altarity, University of Chicago Press, 1987, p. 246

11 Thomas Mical, The Eternal Recurrence of “l’effroyablement ancien,” 1998, HYPERLINK “http://www.pd.org/topos/perforations/perf20/mical.pdf” http://www.pd.org/topos/perforations/perf20/mical.pdf, page 6

13 Giles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, Columbia University Press, 1995, page 7

15 Giorgio de Chirico, Manuscript from the Collection of Paul Eluard, from “Appendix A” of James Thrall Soby’s Giorgio de Chirico, page 248

Read Brian George’s Maps of the Metaphysical Double: In the Footprints of de Chirico, an excerpt from his essays and dramatic monologues on Giorgio de Chirico. It appears on the Finch as part of our ongoing series, Sensational! (Theory by Other Means.) We are grateful for his permission to reprint parts of his manuscript here.