Looking up, I find that my fear has now attached itself to the walls of a museum, where, inch by inch, I search in vain

A Note to the Reader

Brian George

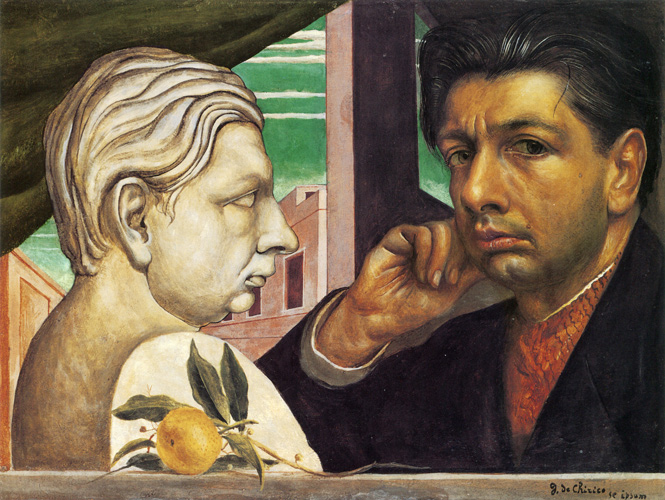

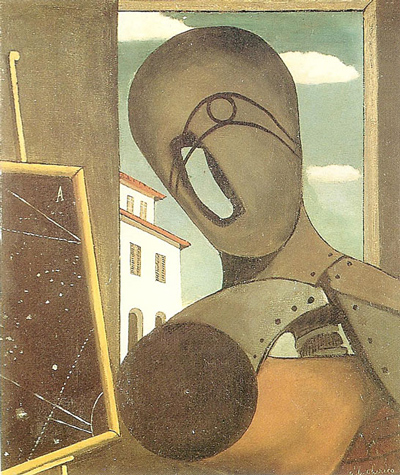

In the following prose poems, I speak through the persona of Giorgio de Chirico. This may not always be immediately apparent, since I frequently have de Chirico speak in the third person. For example, when you read something in the book like, “It is almost certain that the artist who created the first god did something of importance wrong. De Chirico will soon intuit the mistake,” this is supposed to be de Chirico speaking about himself. I don’t think that de Chirico actually refers to himself as “de Chirico” very often in his essays or autobiography, but in Hebdomeros — his 1929 dream-novel — the protagonist is very clearly de Chirico’s alter-ego, and he speaks of his activities with a great degree of bemused detachment. This frees him up to say some truly bizarre and other-worldly things. By being both one with and other than his protagonist, as well as by playing the role of Other to the rest of the human race, de Chirico can move with disembodied ease between even the most contradictory of elements. At once grand and absurd, philosophical and self-deluded, ironic and sentimental, heroic and neurotic, arrogant and wide open to experience, Hebdomeros is nothing if not unpredictable. Nietzsche said, “I was surprised by Zarathustra.” We may guess that de Chirico was no less surprised by Hebdomeros.

+

There are countless examples of the liberating effect of the third-person point of view, in which the author seems no less anxious than the reader to discover what his character will say. Unfortunately, the length of de Chirico’s sentences and the complexity of the scenes described make the majority of these somewhat difficult to quote. Let me nonetheless pick a passage, almost at random, which will give a sense of the infinite recursion of Hebdomeros‘s mode of self-awareness and hint at the originality of the insights that result. So: on page four, after wandering through the back corridors of a building that reminds him of a German consulate in Melbourne, Hebdomeros and his two companions — who are described as “strong, athletic fellows carrying automatics with spare magazines in the pockets of their trousers”1 — find themselves at an upper-class social event. “As though in the face of danger,” the three hold hands, and imagine that they are passengers on a highly advanced submarine, through whose portholes they can observe the plant and animal life of the deep. Hebdomeros notes that

+

Similarly, my use of this theatrical mask allows me to explore and then to say certain things that I might say differently, or not at all, as “Brian George.” It seems clear that de Chirico recognized, and was not altogether comfortable with, the other-than-personal origins of Hebdomeros, with its labyrinthine dream-grammar; with its endlessly collapsible cities that can be unfolded, like a planar version of a cat’s cradle, to reveal a different scene, in which year, cast of characters, and continent have been rearranged; and with its casual perfection of a type of hallucinatory brinksmanship. He did not attempt another work in this genre, and, for the rest of his life, he tended to speak of the book with a certain degree of belle indifference, as though he had played a supportive, rather than a primary, role in its production.

This sense of the artist’s willful disconnection is apparent even when it comes to the publishing history of the book. After its publication in 1929, when it was feted as a one-of-a-kind masterpiece, with some of the most enthusiastic cheers coming from Andre Breton and the artist’s other enemies, the book remained, as John Ashbery says, “unobtainable and all but unknown until 1964,”3 when a new edition was issued in France. On this side of the Atlantic, the story is even more peculiar. Published in an edition of 500 copies by “The Four Seasons Book Society, New York” in 1966, the book did not credit any translator, and, when researched, it was found that “no such publisher existed at the Fifth Avenue address supplied inside the ‘Four Seasons’ book.”4 The book also carried a printer’s mark from Belgrade, which led to a dead end. “Its provenance remains,” writes Damon Krukowski, “as befits Hebdomeros, an enigma.”5

+

While de Chirico, the person, whether as Grand Metaphysical Superman or Combative Anti-Modernist, was quite happy to present himself to the public as an Egotist, we can also observe a process of almost infinite recession or self-removal taking place. We could interpret this, perhaps, as an unconscious version of the Vedic “not this; not that” method — i.e., that the primal self is “not this; not that” — so that the writer seems to be writing himself out of the text, just as the painter seems to be painting himself out of the picture. Like Nietzsche, de Chirico, as Hebdomeros, must dare to go too far. This would seem to be a matter of principle. Hebdomeros is impelled to speak in

+

In his painting, too, we can observe this process of self-removal to be at work. Quite often, for example, the later de Chirico would declare that a masterpiece from the classic 1911-1920 period was no more than a pathetic fake, or that a forgery, done by another artist, was real, or that one of his own imitations of an earlier work, done, let’s say, in 1936, had actually been produced in 1917.7

+

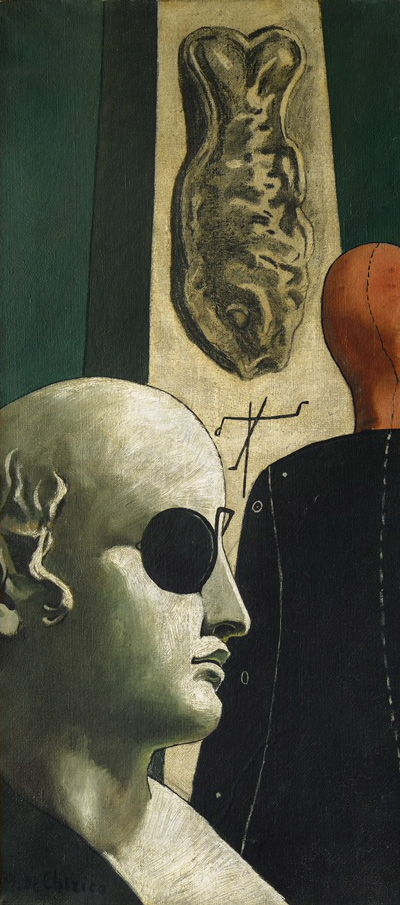

35 5/16 x 16 inches. © Artist’s estate /ARS. Photo: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice. Please see our Fair Use disclaimer.

As far as it goes, the above description of self-removal is quite accurate, I believe, and would normally be understood in terms of literary and/or artistic strategy: It can be useful, and quite liberating, to pretend. It makes sense to assume an identity in keeping with the particular work at hand. If one desires to immerse oneself in an alternate version of reality, one might, to preserve one’s sanity or health, then choose to detach oneself from the power of the archetypal forces that one has somehow set in motion. Yet there is also a stranger perspective that we might do well to consider: It is always possible that Giorgio de Chirico was himself a kind of mask, employed to great theatrical effect, by a daemon who was not born with him at Volos, on July 10th, 1888, and who did not pass away with him in Rome, on November 20th, 1978. Even now, with Maps of the Metaphysical Double: In the Footprints of de Chirico, this daemon, whose focus we might reasonably assume to be less personal than collective, may be continuing to work on a project that he had started long ago.

Brian George

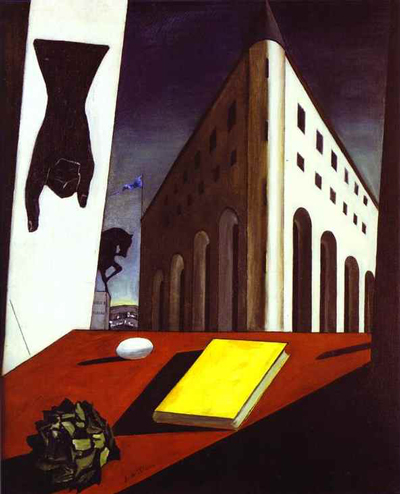

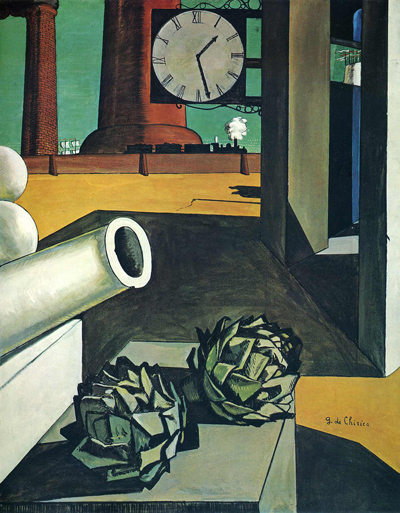

By a yellow van at sunset, a young girl with a stick drove her iron hoop. “However brief, may life grant you all manner of abundance!” I said. Some darkness in the van was waiting to emerge. There was a stone block on the corner. I sat, and unmoving, wept. It was 1912. The beast ate the labyrinth, leaving, where its corridors used to be, only mud-filled trenches, and a thread that I alone could follow to the exit. There, with her paper-mache head, my Muse awaited me; on her brow, a parabola, which intersected with the arcs of several comets. A bell swung back and forth, its echo fading into silence, as the scent of blood renovated the geometry of my vision. Before its end, how intimate the world was! Already, a full two years ahead of time, and disturbing my sleep, the archduke had been shot in Sarajevo; a great tragedy, of course, but also something of a farce. The two hands of a clock had been waiting for the sacrifice to commence, at 11:03, as scheduled, on the morning of June 28th.

Let us now return to that period, during which I came of age. The whole world then appeared to be convalescent, while I, after being sick for months, had more or less recovered. And so: a shadow points to the object of my fear, as it stretches from beneath my feet, but I cannot distinguish between the figure that is pointing and the object at which it points.

In the old days, it may have pointed at some gladiator in a beast mask—a rubberized Taurean one, perhaps—who snorted as he attempted to cut off one’s arms and legs. One could then do one’s best to kill him. Life was simple, even too simple, like a dream from which it was still possible to awaken. This would be preferable to the experience of being sucked toward the horizon, where one does not have a torso, even, let alone a butter knife, to then be sent back to a somewhat different Earth. Each version DOES but also DOES NOT resemble the other, like the same object seen in one’s own and in one’s brother’s dream. At the far side of a web of contradictory perspectives, I can feel time curve like a figure eight.

Looking up, I find that my fear has now attached itself to the walls of a museum, where, inch by inch, I search in vain for some Doric capital or Ionic pediment or Roman arch. It is difficult to believe what I am seeing! At length, no longer just anxious, I am forced to admit that I am scared: some stranger has reproduced the complete works of de Chirico, the majority of which I have not yet managed to import. Then too, I am powerfully annoyed. Many centuries in the making, each painting comes complete with an almost infinite number of variations, series upon series, and now that I, Giorgio, am beginning to get some part of the credit that I deserve, this shadow shows up and claims to be in charge. It is he who has selected this particular venue for my work: It is an odd and, almost certainly, inappropriate museum, shaped like a chambered nautilus, with a 12-part skylight and a spiral ramp. Up and down the ramp, wandering, there are many bags of wind that resemble the one that Aeolus had once presented to Odysseus, saying, “Cut here, on the dotted line.” These all too solid ghosts are full of second-hand opinions on de Chirico, but it is the substitute that interests them, the shadow version. After decades of fighting a pitched battle against decadence, it would seem that I have become a “High Modernist” after all!

As we become more fully acquainted, I must confess that the shadow’s viewpoints are, if not impeccably original, then at least, in many cases, difficult to distinguish from my own. There are times that even my mother cannot tell one of us from the other and, instead of stepping on my shadow, steps on me. Being a worshiper at the stone foot of the Classics, this tends to make me upset. No human foot should be stepping on a genius! It is also my firm belief that the infinite has a form; this form, as it so happens, looks 100 percent like de Chirico, which my mother, if no one else, should almost certainly be able to recognize. It is possible that her puzzlement may have contributed to my own.

Like mine, the shadow’s nose is large, the better to perfect the art of olfactory navigation, which, in the Ancient World, was not the exclusive province of the dead. He will take no prisoners, and suffers no fool gladly. In order that, at some point, he might repurpose it as a boat, he has deconstructed the mechanism that carries the sun west. There is one moment, only. His return to it is eternal. I am somehow swept along. No sooner have I brought my oeuvre into existence than I am forced to paint each masterwork again. Each thing partakes in the aura of Necessity, but why, over the next half dozen years, must eight million soldiers and 12 million civilians die? The clock’s hands do not move from the numbers at which they point, so it is difficult to determine what the time might actually be. It makes no sense to argue that this quantity of blood could have come from the Archduke Ferdinand. Touching his nose, my shadow points to the angle of the sun.

If the shadow is not housebroken, and is not, exactly, a mirror image or a brother, he is nonetheless a kind of gateway to the world. If he is guarded with his words, we should not assume that his silence is not a form of communication, and, if he is careless with our safety, this does not mean that he is indifferent to our welfare. Other presences, although supernaturally vast, would appear to be less benign. If blindingly bright, they are also, in the end, far less aware of their darkness than the shadow is, and their lust for oceanic violence can strike one as almost quaint. There are many hands that seek to insert themselves into ours, quite often without obtaining our consent. The records having vanished, like the leaves that a storm has taken from a tree, they are free to invent whatever laws they wish to prohibit us from stating that their authority is absurd. We should no doubt have propitiated them; instead, they have come in search of the blood that we had thought to keep for ourselves. Our blood has tempted them, and, drawn to it, they have suddenly found themselves on the wrong side of each mirror, with no way to get back.

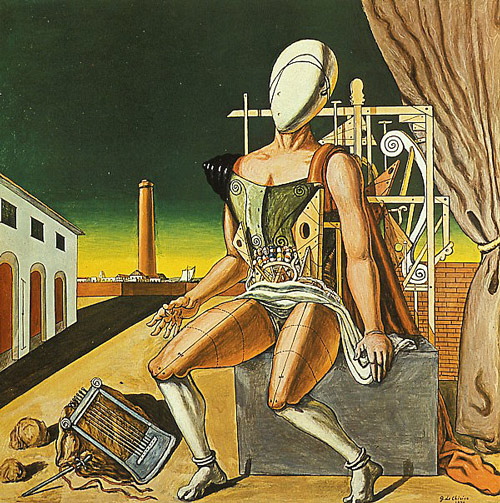

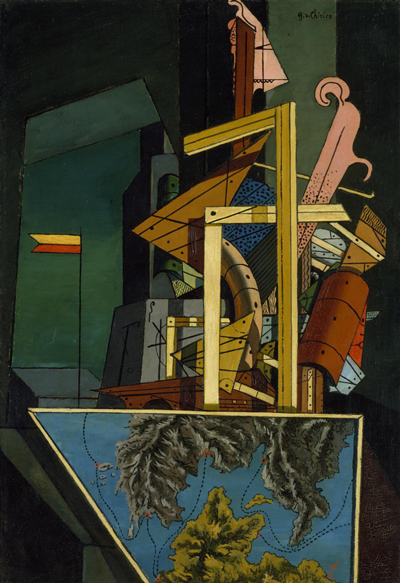

New, but not improved: the gods. Those who were stars now stagger as they go. They are no bigger than we are; no, not at all, and it is only their appropriation of the arc-lights that leads us to perceive them as gigantic. Once, humans and gods were almost equal in their powers, with humans having a slight edge. They had fixed their eyes upon the best seats in the stadium. We liked to jump from cliffs. It is we whose hands once sculpted them out of lumps of unformed plasma, only to have them steal the breath out of our mouths. It is our breath that inflates their symbols. They have always been pretenders. Some catastrophe has now overturned the fixed order of the Zodiac, of which industrial-scale slaughter is both the cause and the effect. Our masters now turn into helpless infants, while, again, our race matures. On the top floor of a factory in Turin, I wake to find that I am staring at a blackboard. Birds demonstrate the toroidal genius of the manikin, whose head, with all of its features, they will teach us to turn inside out. That the mechanism of our own heads is so similar is no doubt a coincidence. A soft wind blows through the jagged glass of the windows. I can smell salt in the air, and a dangerous new confidence begins to pulse in my bones. We slaves will give birth to the technology of Atlas. Heart, be quiet! It is the hour of archaic joy.

Brian George

Pregnant the figure eight that I drew on manikins abandoned upstairs at the factory! We servants of the infinite had traveled far from our own coast, on our shoulders, bags of cities that looked like common seeds. Now, in the last days of the planet Saturn, as the boom of the big guns echoed and then faded, we could do little more than gesture in the language of the deaf.

The two hands of a clock told perpetually the same hour. They were right at least twice a day. A shadow asked, “How many dead are there?” I answered, “Thank you. My wife is well.” On my doorstep, I found that the Argonauts had left a rubber glove. It was no doubt waiting years for me to bend over to pick it up. I did. It fit like a glove. How odd that Phineas, son of Agenor, chose that same day to return to me the eyes that I had years ago so carelessly discarded in Ferrara. Taking sunglasses off, I felt them fly back to their sockets. I could see to the end of the street.

A few leaves blew. I wandered through the stillness of an autumn afternoon in Europe; they watched me enter the square. The clock’s hands had stopped at 3:15. Once again, it was almost time to go. Each autumn afternoon I walked through the arcade. Because I was alone intelligent, I had made good friends with others. Drop by drop, fell water from the lip of the ruined aqueduct. “Cupid, you’ve got moss in your mouth,” I said, “Take it out, or I will scrub it out with soap!” In my hand, I discovered that I was holding a spool of thread. It weighed more than an asteroid. Divergent the lines of perspective that still somehow meet in a point. Birds flapped around my head. It cracked apart. I had not been the same since mother died. For someone so intelligent my back hurt.

At midnight, I got scared. I was the necromancer of the Cyclades! The numbers one through 10 from lava built the antediluvian state. Its adamantine columns towered to the stars. Their power vast, its inhabitants were younger than my dreams. They were not yet subject to the hand of Ob. In those days there were giants on the Earth. I alone have escaped to tell you, but there was no one to give the message to.

Perversity of the psychopomp! I had discovered Zero—or so I thought. Fast forward time was sent back in a circle to the factory that made it. The day was a resounding nautilus. From a smokestack puffed a puff of smoke. It rose. Pink and green, the pennants fluttered on the towers. The pennants brought me joy. I could smell salt on the air. A big bunch of bananas waited beneath the arch. I could see my paper sailboat bobbing in the harbor. About prehistory—the truth: it echoed. The nose broke on the oceanic statue. Sing muse of the inanimate that petrified the Cyclops in the square. I clung to the horizon with my breath, as to a thread. It was the day that I learned of the miraculous birth of vertigo.

Silence echoed down the arches by the factory of prosthetic limbs. Above the city, the hand of the industrial founder was enormous. “Let go of that net,” I said, “that has pulled in all of the toys from the main deep! That net belongs to me, Oannes!” The sun was cold. The wind searched for a city that never did exist. Strangely, I had found it.

When I wandered through the railway station, said others, “He is lost.” “No,” I said, “it is you the stranger who are strange. I am the scourge of Edom’s kings, the ithyphallic poet in a fish suit. A new light dawns above the ruined city. Europe, praise my book, “Hebdomeros!” The import is: you are exports. Do you not recognize your relative? Stranger, who are YOU to call me strange?” From a height, I saw that as it happened long ago. I experienced departure. The crowds left for their appointed tracks.

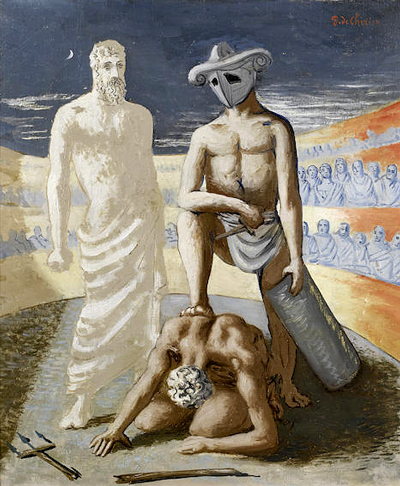

© Artist’s estate /ARS. Photo: MoMA / Wikiart. Please see our Fair Use disclaimer.

The depot was not different from a wharf. You could hear the small waves lapping at the exit.

Smoke assaulted me. Factories that put shoes on the revolution smoked. A puff escaped the stack. “It moved. It should not move. Stay put and let the Earth move!” I said, “Throw the migrants out. They do not speak one language. Birds stoke the ruins of Ionia with blood. I am just a boy.” Thebes was transplanted. The mid-Atlantic flamed.

“Stone engineers, though silent, please: wash up on the beach,” I said, “Give praise to Hygenia, the muse. Io! There are bird lamps in the cave! I have diagrammed the labyrinth. I have dragged to my apartment the stalactites.” The Library of Alexandria would soon be swept off by the wind. Art is short. Life is long. I set up my ironing board to brew a cup of java. When I thought about mother I got sadder than a sponge. I slept for several days, my eyes wide. I then went out for a walk around the roof. For someone so intelligent my back hurt.

As I stared at the thin line of the horizon, I could feel eyes probing into the back part of my skull. “O infinite extension of the astronaut,” I said, “I see through you. I confront perspective. I laugh to see that I am taller than the giants, who are not as strong as ants. I promote the paradox of the five Platonic solids: how out of one comes ten, one half of which is more perfect than the total. Occult triad: I excuse you, and exonerate your stealth. I celebrate the enigma of the fatal hand.”

My memory is good. I am the child of an engineer. Thoth rubbed my head. I took a piece of candy from my bag. “Would you like one dad?” I said. “No. In your sailor suit you will supervise the construction site on Mars.” The clouds roared north. For several years I slept in a crate. “I, Hebdomeros, do not believe that bugs should eat my bandages!” I said. Autumn leaves blew. I walked straight through the shadows of the long arcade. The Eternal returns—with its own agenda. O Achilles’ tendon! Hector’s foot!—: you both fall victim to the storyteller’s voice.

Are the Many real, or do I intimately possess the organs of each soul? Dad’s hand was large. His chin grew. His smile had teeth. He had hair on his chest. He left the Earth when I was young. It was October 23rd. The shadow of the dead: enormous. That day I went out for a walk around the bull’s eye that was Turin. On the square I found a sphere. It petrified. I went a different day. There was a strange van in the square. From it, I could feel the heat from a dead sun. It became apparent that the creators had long since vanished into their work. Out of revolution, stasis. As I wandered through the silent city, I found that I too could not help but be silent.

I knocked on the door of the Castella Estense. They gave me a piece of bread. I was as famous as a god! They had heard about my work. “We are sorry that you have to go,” they said. When I turned, the door’s frame was the only thing that stood.

A big bird took my hand. “Do not sleep now. We have far to go!” Chug chug went the locomotive bound for North America. I saw the future speeding backward, love. It had a body like yourself. Birds told me that I was good, but I COULD NOT find a grave on which to pee. The inanimate marched post haste over Rome. Shoe stores took a quantum leap. The men in black were played by their pianos. Sun spots reproduced the bad art of the demiurge. Vicarious, the voices bounced. Mechanics monkeyed with the Island of the Dead.

I got sad when I looked at shadows on the piazza. The zodiac shuddered like an opened cage. The birds had left before the Pleistocene. “Eurika!” I said. As we, each in our own sub-lunar holocaust, conversed, the birds showed me how the figure eight is not, in fact, that different from a city. Nostalgia for the first race broke my heart. I could not return, for I had never left.

Large buildings rot. Black ladders span the void. I wandered through a map that was the same size as the city. For someone so intelligent my back hurt. A bird said, “Take my hand. The Eight will see you through this autumn day.” I got off where they showed.

1 Giorgio de Chirico, Hebodomeros, edited by Damon Krukowski, Introduction by John Ashbery, original in French, 1929, according to editor, translator remains unknown, Exact Change, 1992, 2

2 ibid., Exact Change, 1992, 4-5

3 ibid., “Introduction,” John Ashbery, Exact Change, 1992, x

4 ibid., “Publisher’s Note,” Damon Krukowski, Exact Change, 1992, vii

5 ibid., “Publisher’s Note,” Damon Krukowski, Exact Change, 1992, viii

6ibid., Exact Change, 1992, 111

7This is not so much a reference to a particular declaration by the artist as a summary of a general pattern of behavior that has been researched and analyzed by many critics. Here, for example, is a comment by Emily Braun from her excellent essay “A New View of de Chirico.” Many other critics could be cited.

“Certainly the greatest obstacles to the authentication of de Chirico are the artist’s habit of making copies of his own work, especially after 1940, and his capriciousness towards the art market. To begin with, one must distinguish between copies by his own hand and forgery by another’s. Future scholarship will also need to prove, as defenders of de Chiric’s integrity maintain, that de Chirico himself never forged his own work; that is, he never replicated images with the intention to pass them off as the original for financial gain. Instead, details of signature, dating, brushwork, compositional variations, and iconographic inconsistency give sufficient evidence of de Chirico’s play with pastiche, parody, and the concept of the copy. The debate as to whether de Chirico was a dishonest profligate or a brilliant strategist will continue until the subject is thoroughly explored by means of an object-by-object analysis; a full accounting of the forgeries perpetrated by others; and the damage done by de Chirico himself in the haphazard and, at times, deliberately contrary authentication of his own work.”

Emily Braun, “A New View of de Chirico,” from De Chirico and America, Hunter College of the City of New York, Foundazione Giorgio e Isa De Chirico, Rome. (Turin: Umberto Allemandi & C., 1996: 14).

Poet and essayist Brian George lives and works in Boston. Read the first installment of his series, The Snare of Distance and the Sunglasses of the Seer on Metapsychosis.

Brian George’s Maps of the Metaphysical Double: In the Footprints of de Chirico, essays and dramatic monologues on Giorgio de Chirico, appears here as part of our ongoing series, Sensational! (Theory by Other Means.) We are grateful for his permission to reprint parts of his manuscript here.

Read Brian George’s “The Artist as Blind Seer: A New Perspective on de Chirico” here on the Finch.