I have always liked the Latin phrase ex nihilo

Jen Mazza

Simple enough.

Destruction takes place at the point of maximum awareness.”

That which withdraws from view, from understanding — in light, in shadow, in absolute darkness —

Robert Ryman’s white paintings and the Samuel Beckett Trilogy3 link in my mind in a question about seeing; link over light and darkness, in the perception of the real — both in the seen and in the understood, and in the misseen, misunderstood — illumination, or the lack of.

Ryman insists on speaking about “real light”, just as Donald Judd insisted on using “real space”, yet what the real evokes is perhaps something even more untenable than illusion: that which exists at the place where metaphor fails.

This statement by Clement Greenberg about Judd’s work could equally be applied to Ryman’s paintings.

The point at which metaphor fails is, of course, the moment when language fails, when what is cannot be defined. Beckett also wanted to undermine the desire for and the presumption of clarity. He often employed an obscurity of meaning. He reminded us how truly inarticulate language can be by indicating the imperfections of our own subjectivity, such as the darkness offers us — the audience — in this particular staging of three short plays.

In Lisa Dwan’s production of the Samuel Beckett Trilogy, all the lights are turned off: no aisle lights, no exit sign, no glow of the entry hall slipping through a cracked doorway. So I am first confronted with the experience of true darkness, something so very unusual to find in a city — and then I become aware of the action of looking: a striving, not to cease seeing, but with eyes active so as to see. I have always liked the Latin phrase ex nihilo, “out of nothing”. Out of nothing, the actor appears on the stage. In Footfalls, Lisa Dwan appears treading back and forth across the stage. She is a ghost in the less than half-light. Again I am aware of the action of looking, feeling it in the eyes, the strain to discern. My eyes are discontent with the spectral, the form in flux, the form almost having no form. The lack of light plays disorienting tricks on perception. The eye does not know what it sees and what it manufactures, sees the very detritus of seeing — ex nihilo, out of nothing and then a return, into nothing.

The things that emerge — in light, in shadow, even in absolute darkness — one would think that at least in complete darkness there might be an absence of image, a freedom from looking. Plotinus said:

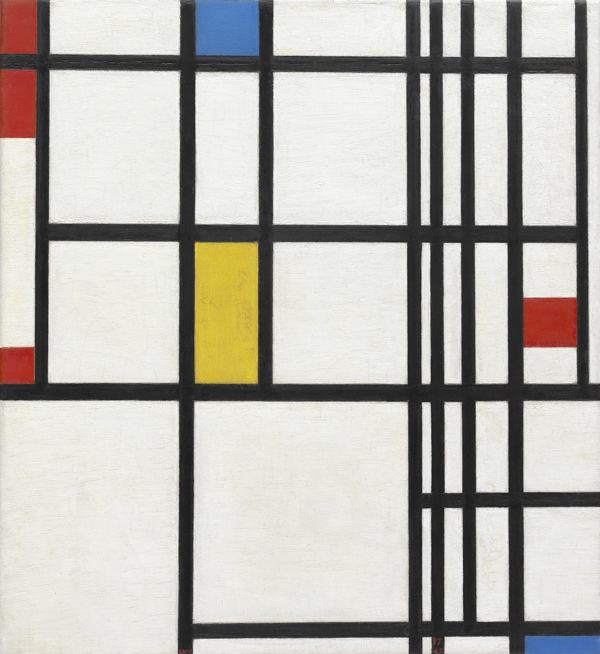

A pale form in a white dress…yet is it even white? If there were color, the absence of light would suck it away. A pale form in a white dress becomes a screen on which image and afterimage superimpose. Even thought itself becomes as active a participant as the Real, as the mind projects a mirage of meaning and form onto the amorphous. And yet all this eye-noise interferes with coming into understanding and the desire to define which might be served better by the eyes’ power of not-seeing. As poet Rosmarie Waldrop puts it: “this not-seeing / sees the night”. Perhaps we are meant to navigate by this spectre: steer our eyes by it rather than towards it. It is said that moths navigate in relation to the moon by a transverse orientation and yet those blooms that rely on night’s pollinators are also white or drained of color. A white rose in the night garden is just a small grey spot; draws eyes like moths, but in the figure on the stage the geometry of bone anchors, creates structure. “Form imposes, structure allows,” writes the poet Charles Wright, and later on he says: “Mondrian’s window gives out / onto ontology”.5

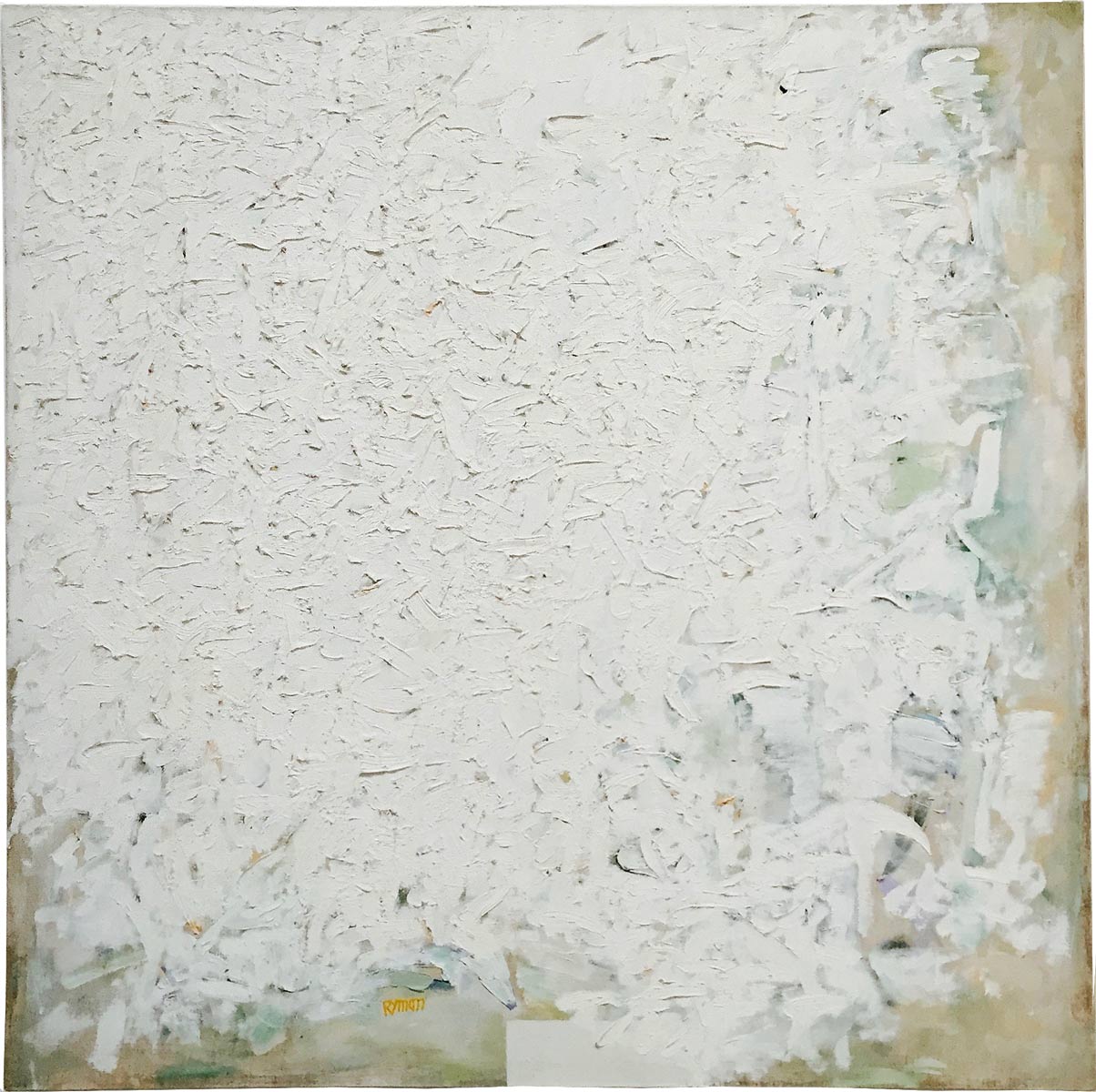

What is seen? What is known? How to be certain? Still, in the pale spotlight, structure imposes an order. Where the actor’s eyes fail to glitter, sockets are dark and skin seems to fall away to reveal bone. Shadow dissolves flesh to reveal the cruciform pattern of the skull with its verticals and horizontals. I think of this as I stand, 16 hours later, in front of Ryman’s Untitled, c. 1960. It’s my second visit to the Ryman exhibition at the DIA Arts Foundation in Manhattan. The cruciform pattern of brush strokes seems to, at a distance, encourage the eyes to define. I have noticed recently that I have been attracted by the faces in things, faces that are not faces. For years I stared at the Felix Gonzalez Torres poster6 at the foot of my bed and it stared back: I let my mind impose such faces upon the waves’ patterns of light and shadow, and now, even within my own work, I do not disrupt the faces I find, but press them into a greater clarity. To do so seems a deliberate thwarting of the tasteful. I am suspicious of good taste, its leveling effect on meaning. In Ryman’s painting the ridges and ruts leftover from the brush separate into brow, bone, socket, lip, line, tooth, bridge, chin, jaw. Today, an April afternoon, the sun is bright and the surfaces of the paintings are composed of light and shadow.

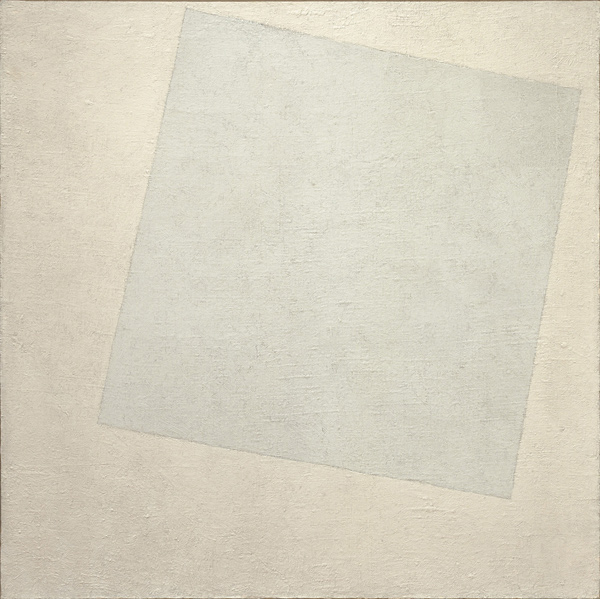

In addition to the Ryman paintings at DIA, I have been visiting Mondrian and Malevich‘s paintings at MOMA, specifically to look at the way both artists used white — its function and application. I notice my mind tends to make the same assumption the reproductions make: the assumption that both artists made smooth paintings. Conservators in the 1950’s evidently made this mistake as well and when relining the paintings they “ironed out” the impasto.7 White pigments, titanium especially, that great cover-over-er, can take such a long time to dry. I find a place where Mondrian closed off a white square with deep visible brush marks. He was clearly impatient to complete the geometry and solve the shape without masking by simply rerouting the final strokes to the horizontal. In his haste he let his hand be seen, perhaps he foresaw, and even counted on, the ironing out that would take place in the reproduction?

Malevich also must have built up paint quickly, each layer of strokes subtly undermining the direction of the underlying strokes, raking the surface: wet thick paint over wet thick paint, so that the brush did not cut through the previous layers still wet, so the strokes float over each other in time and space. Brush strokes are embodiment, they link the artist to the viewer. The strokes move the eye across the surface: weave body and time. I stand longest in front of Malevich’s Suprematist Composition: White on White (1918). A geometric figure, a sort of square floats in the right corner of the larger ‘square’ of the composition. Malevich’s geometry is never perfect, hence the tension and the illusion of movement it provokes. There are two ‘whites’ in this painting. The square of the canvas is filled with a warm, greyed out butter-toned white, while the interior square is cool, almost greenish by comparison. In many of the Ryman paintings, as in those by Malevich, one becomes aware of the artist’s hand at work — how a mark changes progress across a surface, not arresting movement, but instructing it in its flow, measuring it out in increments. The impasto records each press of paint against the surface, repeated gestures that in both White on White and its looser cousin, Ryman’s Untitled #17 (1958) approach, but never quite reach, the penciled/painted contour of the forms that contain them.

The use of white focuses the viewer on the tactile — on the paint itself. It is tempting to see the subject of these paintings as the very process of painting itself. But this simplistic reading overlooks a great deal. There always seems to be a point at which the meaning of a work of art is insoluble in language. There is a kernel that does not break down, that remains within the mind as an object within itself: something to be seen from the outside, but which the light of thought cannot entirely penetrate. This causes a desire to turn and return to that which we have seen: be it a painting or whatever container offers the unresolved truth — the truth in process of becoming — to search and research its aspect for clues or conclusions.

Beckett (says to Duthuit) — The expression that there is nothing to express, nothing with which to express, nothing from which to express, no power to express, no desire to express, together with the obligation to express.

A friend (turning towards me says emphatically) — The thing in itself!

Beckett (turns and looks at the painting) — On its what is the wrong word its uptilted face obscure graffiti.

Ryman Painting —

Beckett — (exit weeping)8

What is the wrong word? White? Where does meaning stick? Where is the assumption that circumscribes the undefinable and oversimplifies? Perhaps “white” is the wrong word. “White” even being a word suggests that its meaning is resolved. And yet “white” is always visibly unresolved: word as figment, color as figment. Can this be what Courtney J. Martin suggests in the DIA pamphlet when she writes, “As viewers, we experience these painted frequencies of light as white…”? This sounds very noncommittal, ambiguous; and yet truly each white is as mutable as the natural light that filters in through the skylights.

The color white was for Malevich the color of infinity, and signified a “realm of higher feeling”. And like the concept of the infinite, the “color” of white has something intangible about it. Are we not told that white is the presence of all colors? White reflects back the whole of the visible spectrum. A color that is all colors and no color: white is a deceiver, a backslider, the double-crosser of the visible spectrum. Or else white is so credulous and wide eyed that it is taken in — easily influenced by its milieu: and so on the spectral scale it can be swayed and tipped in favor of one or another of its prismatic comrades. The perception of white is in fact dependent on, or influenced by, the presence or absence of another color nearby. White tints itself to the light and becomes a pale mimic of whatever is near.

I wanted to watch the Ryman paintings blush when I first visited DIA in February, I wanted to infect them: purity tinted by my own presence, the very manifestation of uncertainty and influence — and through this act to urge something concrete, even fleetingly, onto the surfaces. But there was hardly any natural light to speak of. “Real light” withdrew from the paintings on this winter afternoon and all the whites slipped into a twilight of grey and caught no reflections. Yet still, on this occasion I took copious notes. But reading over these notes two weeks later I decided I had seen nothing and so in fact my notes said nothing: ill seen ill said in the half-light of a dimming February afternoon. In the absence of light I saw only with my moth eyes. I bounced off the surfaces. I bounced off meaning. I threw away the notes.

“If there may not be no more questions let there at least be no more answers.”9

1Charles Wright: Sitting at dusk in the back yard after the Mondrian retrospective, Negative Blue (NYC: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2000), p122.

2Samuel Beckett, Ill seen Ill said, (New York: Grove Press, 1981) p21.

3Robert Ryman (an exhibition at Dia Art Foundation, December 9, 2015 – July 31, 2016) and the Samuel Beckett Trilogy: Not I, Footfalls and Rockaby (produced and acted by Lisa Dwan, staged by Walter Asmus, Skirball Center, NYU, April 13th, 2016)

4Clement Greenberg speaking about Judd’s work in “Sculpture in Our Time” (Arts Magazine, June 1958)

5Charles Wright, from the poems: “Sitting at dusk in the backyard after the Mondrian retrospective” and “Summer Storm”, (Negative Blue p122 and p61.)

6Felix Gonzalez Torres poster: Untitled, 1991, offset print on paper, endless copies.

7See Malevich: Painting the Absolute, Andrei Nakov (Farnham: Lund Humphries, 2010.)

8Three Dialogues by Samuel Beckett and Georges Duthuit, p113 and p103. Ill seen Ill said, (New York: Grove Press, 1981), by Samuel Beckett, p44.

9Ill seen Ill said, (New York: Grove Press, 1981), by Samuel Beckett, p43.

Painting from Jen Mazza’s recent project Open Letter is current featured in Objectivity, which runs through July 29 at Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York.