…deeply painted, bathes shapes in air and carries the eye around the back of the form…

(Citation)†

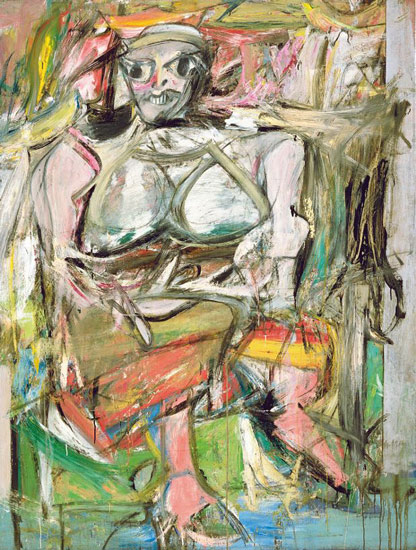

But de Kooning’s work was another matter. It was clearly based on categories of figure and landscape, and its formal properties — the sense of edge and line, its concern with weight and definition of form, and its figure–ground contrasts — came out of an engagement with the Old Masters and a tradition of studio practice which Auerbach recognized at once. The Dutchman’s hooking, rhythmic line evoked bodies in the jostle of elbow–forms and crotch–shapes, and drew them openly in the totemic Women. His paint surface was a membrane, now thick and now a wash, but always under some degree of torsion and tension from the boundaries of the forms. And the linear qualities of de Kooning’s style were embedded in the swiping of the brush; the gesture and the form were one. At the same time there was enough contrast between figure and field in his work to give Auerbach’s figural obsession a handle on it.

In sum, Auerbach found himself admiring in de Kooning what he admired in Soutine — the sort of draughtsmanship which is deeply painted, bathes shapes in air and carries the eye around the back of the form, rather than leaving it with the contours and colour of a flat patch. If any American artist of the 50s seemed to Auerbach to have matched the terms of Bomberg’s ‘spirit in the mass’, that person was de Kooning. The example of Abstract Expressionist gesture did not wreak a sudden change in Auerbach’s work, as it did in other English painters like Peter Lanyon and Alan Davie at the end of the 50s, boosting them out of their Cubist framework. Instead it was slowly and cautiously absorbed, slowed down by the thickness of Auerbach’s surface, which it energized in terms of vectors pushed through the paint — directional brushstrokes which wiped aside the clutter of pentimenti under the paint-skin. The first work in which this became clear was Shell Building Site From the Thames, 1959, a view down into the deep cut of the excavation for the skyscraper.

+

The perspective of the floor of the hole, with the stumps of steel columns and the clay side rising to a high horizon line, dominated by the kite shape of a crane’s raised booms, is done entirely with broad directional brushstrokes, furrowed and mucky but still insistently linear. It is spatially open and conveys a sense of air (or if not air, at least some variation of near-and-far substance). It is perhaps the first painting of Auerbach’s that seems to have been done quickly, even though the look of speed is an illusion.

†From Frank Auerbach by Robert Hughes © 1992. Reprinted by kind permission of Thames & Hudson Ltd., London