I believe there is no progress in art.

(Citation)†

I believe there is no progress in art. We might complicate things by introducing new materials and new techniques that make possible new modes of expression, but the art of recent centuries isn’t better in quality than the best of what was made throughout history. And it isn’t new.

+

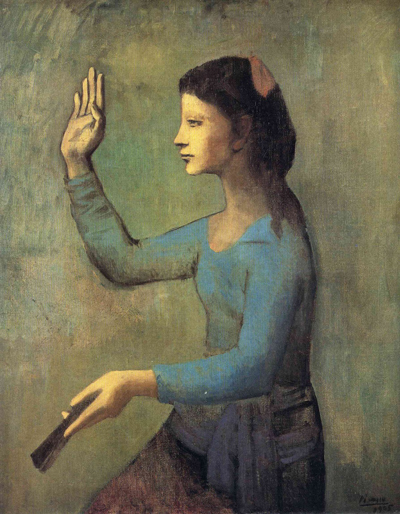

In my slide talks I often start with a slide of a cow from the Lascaux cave paintings, dated something like 17,000 BC. I talk about how that cow is is unsurpassed in translating observed nature into an elegant and refined understanding of the essence of a particular animal. I explain how it is as sophisticated in terms of drawing as any cow in the history of art. Of the many different kinds of drawn or painted cows none are better than that Lascaux cow. They are just different. 16th century Dutch painters like Aelbert Cuyp painted cows very beautifully, and Picasso’s much more abstracted bulls might, in their way, be as good as the Lascaux cow, but I can’t say any of those depictions of a cow are better than the one painted 19,000 years ago. For comparison I put up a slide of Picasso’s Woman With a Fan, from 1905, and show the students that what I pointed out in the Lascaux cave painting, that makes clear that the legs on the far side of the cow come from behind the cow’s body, is precisely the same as what Picasso did to spatially separate the forearm of his woman from her torso. In both cases there is a lightening of color behind what is in front to interrupt the otherwise continuous contour surrounding the body.

Then I show a slide of a Cycladic sculpture head from about 2,500 BC and talk about the kind of abstraction the Cycladic sculptures have. I mention Constantin Brâncuși whose abstract figurative sculptures might make the best 20th century comparison. The Cycladic heads have no eyes, which is highly unlikely for any kind of depiction of a head in almost any culture. I have no idea why that was, or how a cave man could draw with the intelligence we can see in the Lascaux paintings. I show a couple of Ancient Roman marble portrait heads from the first century BC to the the end of the first century AD which are remarkable in their realism, and are great portraits. And I show one or two slides of wax encaustic Fayum portrait heads, from the Coptic Egyptians dated from about 160 AD. The best of those are as beautiful as any portrait of any period, anywhere. Ife and Yoruba terra cotta and bronze heads from West Africa in the 12-14th centuries are also unsurpassed in realism and elegance. And they are surprisingly advanced compared to what was being made in Europe in the same period. Ron Mueck, today, takes sculptural realism beyond what Hyperrealist sculptors Duane Hanson and John De Andrea had made a bit earlier. Nobody is making a figure more real than a Ron Muek sculpture (other than to make it in human scale, which Muek doesn’t do) unless you count when Gilbert and George presented themselves as sculpture. And that is a question of how realistic sculpture can be, and not about quality in art.

If we accept that there is no progress in art, and that the kind of brilliance I referred to in a few slides had emerged independently in isolated cultures many centuries and continents apart, we must be looking at archetypal imagery. And perhaps there is an explanation for that intelligence that suggests that we, in our own culture, are less able to create the beauty and the stylistic and symbolic meaning we see in those examples than were the artist-craftsmen of those ancient civilizations, and the so called “primitive” cultures. And maybe that is because we in the West are lost in a confusion of our own making, starting in childhood when we were fed a visual diet of cartoons, Muppets, electronic games, factory made toys, sitcoms with canned laughter, and the rest. (Fortunately, as a child I was not exposed to most of those miserable things produced for children today). How often do we think something factory made has charm, or has the traces of the hand or the mind of someone who designed it? At best a manufactured toy is a prop used in play, and play can be creative. But I don’t think the six shooter cap guns and rubber tomahawks most children had when I was a boy led to anything we would call creative. We are exposed to a profusion of things of mediocre quality and an over-abundance of choices. Fast food and fast other things replaced what could be more meaningful. I could say more inspirational, but that would suggest that there was an intention there that just wasn’t there. We live in a culture of dumbing down, of wanting to keep children entertained instead of allowing them to interact with adults. Not only, of course — but in the formative years of a child’s growth “not only” is still too much.

I explain to the students that although there is no progress in art in the sense of art getting better through the centuries, what we artists can do is make art that is from within ourselves, which is to say it will be different from anything made by anyone else. If it is good it will have been informed by the study of art from various periods. We work with that which interests us most in the art of the past as well as of our time, and gradually, unconsciously, we work with what starts to emerge that is unique to ourselves. And in that, what we make is new. It isn’t likely to be new in concept because lyrical abstraction existed as far back as art itself, and realism as far back as Hellenistic and Roman times, and all kinds of other ideas and styles have been worked with for centuries. What is old in art can remain entirely relevant and beautiful because it is timeless.

+

It may take years to find what we can believe to be our own tendencies and interests and ideas about making art. We do our best to figure those things out while we are in the process of making our own work. In general we won’t learn about our personal vision by means of an intellectual approach. Rather we observe our own tendencies within the art we produce, and paying close attention to what does and what does not hold our interest. Art should reflect the psyche of the artist, and where it doesn’t, it has a fundamental problem. It will be perceived as empty, no more than an exercise in making something. It might be decorative and nothing more. To find what interests us most and to become aware of our limitations, and what moves us and what doesn’t move us, in the art of others, is a slow and never ending process. Our work can have a simple theme, but it doesn’t have to be ordinary. We don’t all live extraordinary lives. We are all interesting and we are not ordinary when we deal with deeply personal material. Few, if any, of us are capable of painting as well as those we try to emulate, but we try nevertheless. We compare what we make to what we consider to be the very best works made by those artists at the top of our personal list of the greatest artists of all time. We don’t think of that as being a formula to guarantee failure. That is not what it is about. It is a challenge we undertake that becomes something we live for.

+

After that introduction I mostly show slides of my own paintings starting with my Gorky-deKooning-Graham influenced graduate school paintings and leading up to those I have been making recently. I show one or two paintings in stages from day one to the finished painting to show how any of my paintings will have gone through many changes. Sometimes I end a slide lecture with a few words about how we should make our paintings extraordinary. That’s something I think students need to think about, and is sounds simple and obvious, but it is not. We have to think about what paintings we find to be extraordinary, and what it is that makes them extraordinary. I show Picasso’s 1919 Still-Life With Apples and Pitcher. And I show a 1919 Morandi’s still-life called Roses. And I show Bruce Kurland’s Bone, Cup, and Crab Apple, of 1972, and Flemish master Robert Campin’s Portrait of a Stout Man, c. 1425. Of course I could use countless other examples but these work nicely. They are all small paintings having as their subject something we might consider to be quite ordinary. The question is what makes a small painting of something ordinary become greater than ordinary.

†From Alan Feltus’s unpublished memoir, now in progress. We are grateful to the author for permission to reprint it here.

Read: More from Alan Feltus on theFinch.net

Sites:

Alan Feltus: www.alanfeltus.com

Lani Irwin: laniirwin.com

Forum Gallery, NY: forumgallery.com