I had a break-through in my painting when I began thinking metaphorically. It started with a vein in a forehead…

Anne Harris

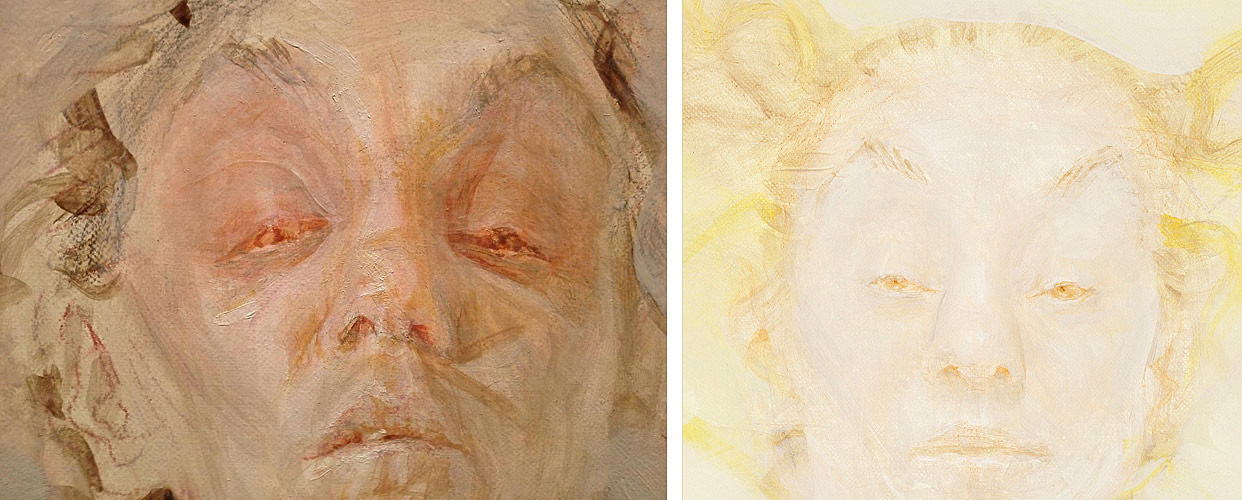

I had a break-through in my painting when I began thinking metaphorically. It started with a vein in a forehead, then the realization that everything could be vascular. So tendrils of hair became capillary, as did tendrils of light, stripes in a shirt were arterial, a scrunchie hairband a thrombosis. This was a key for me to unlocking invention.

Since then, I know I’m rolling when I’m painting inside a metaphor. The eyelid has been a favorite for many years. After all, what is an eyelid? A beautiful surface that is also visceral, a flap of skin, a membrane — it’s fragile, yet designed to protect something even more so. It’s formless, taking its shape from the thing it covers. When closed, dry covering wet, I imagine the fluid beneath compressing, sliding downward. It functions as opaque but is translucent from the inside, light glowing through, and transparent from the outside, tiny blood vessels on view just under the surface. Stare at a shut eyelid and see pure passivity; but suddenly open — we’re shocked!

© Anne Harris. Courtesy the artist and Alexandre Gallery

I want my paintings to function like an eyelid, veering from dry to wet, inside to outside, opaque to transparent, form to formless, mute to aggressive, space curved outward toward the viewer, held in by fragile surface tension, the picture plane as membrane, the entire painting an eyelid.

Photograph: The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Fair Use Disclaimer.

I've wished that I could paint the world’s best eyelids. For me, Ginevra de’ Benci holds that title. Regardless, I am at my most content when painting the skin and flesh that covers and surrounds eyes. I see this as metaphorically functioning in many of the paintings I love. Take Ginevra’s neighbor, Van der Weyden’s Portrait of a Lady. The space is like a lens, shallow pressurized depth pushing against a curve. Paint, skin, and of course her depicted head dress, are veils drawn over emotion, obscuring inner life while still implying its existence. Everything arches forward, the bell of her hands, her forehead, chest, her bowed mouth, the plane behind her, all of it held in check by her inward gaze.

The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

I am mesmerized by work that floats within this realm of transition and contradiction. Connected to human presence, it exists beyond subject matter. I’ve had this same swelling hypnotic experience in front of, among others, Goya and Ad Reinhardt, early Brice Marden, Milton Resnick, Duccio, and Dieric Bout’s Mater Dolorosa, which I visit weekly. She has, I believe, the saddest eyelids ever painted.

The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL.

Anne Harris: Delusions/Illusions opens at Nebraska Wesleyan University’s Elder Gallery on 30 August 2016. (Through 9 October.)

Harris currently teaches in the BFA and MFA programs at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She serves on the board of the Riverside Arts Center and is Chair of its Exhibition Committee. She also is the originator of The Mind’s I—a collaborative drawing project designed to investigate the complexities of perception and self-perception through drawing.

Harris lives with her husband, the photographer Paul D’Amato, and their son Max, in Riverside, IL.

Her work is represented by Alexandre Gallery, New York, NY.

This article first appeared as part of Tilted-Arc.com‘s series, On Process (4/2/’15). We are grateful to Anne Harris for her permission to reprint it.