I like a painting that does something, like a machine does something: you turn it on and it functions —

The click of the shutter, the click of the cliché, but lets come back to that later…

I have noticed that not infrequently, when I find myself in front of a painting I have been introduced to through an invitation or an article online; that the painting in question does not give back anything more in person than the digital image I’d previously seen. It yields nothing new, no new read, no additional meaning. On occasion it may yield something less than its copy: almost seeming to function purely as a painted iteration of the digital image. The digital privileges the retinal.

Photograph: Eric Wolfe.

It is likely I will never forget my interview for the graduate program at MICA when I met with Grace Hartigan. Getting straight to the point she said “your slides read better than your paintings.” Which at the time I admitted as being quite true. I was not, in the end, accepted into the program, but I somehow can’t imagine that in the two years I might have spent under her guidance, that she would have given me anything to surpass this brutal but relevant challenge effected during this brief acquaintance. The paintings I had created were a surface lacking the quality of illumination which the slides possessed, a lack of illumination which often diminishes the paintings I see today in comparison to their on-screen “reproductions.”

This is not a judgment, this is an observation, I think it is likely that this quality in the work reflects something which is happening at the moment, something in and about our time.2 I had been speaking recently with artist Aaron Williams about the great diversity and potential in ways of viewing art today. There are those things that require to be seen in person, other things that don’t, and some things which need not be seen at all; it might suffice to read a description of the work in order to set off a chain of ideas and impressions.

I think all of the ways of being affected by an artwork are valid and interesting, but my question centered around what it was I wanted my own work to do. I feel it likely that I stick to painting because I enjoy the physicality of it, the goo aspect. The way the goo makes the image come over on you, not just retinally, but with the complicity of the eye it works directly on the body to engage many more senses than the one. I decided that in fact, it did not matter to me so much what a painting looked like, but what it did. What the paint depicts certainly must play a part, but it is not an end in itself, nor perhaps even the most important or interesting function of the medium.

I found an echo in the William Carlos Williams statement, “A poem is a small (or large) machine… .” A painting can be a machine. I like a painting that does something, like a machine does something: you turn it on and it functions, and continues to function without your intervention — generating, producing, developing, asking questions, making meaning—it shouldn’t stop, but should continue in its way to function in your mind and body even after you walk away.

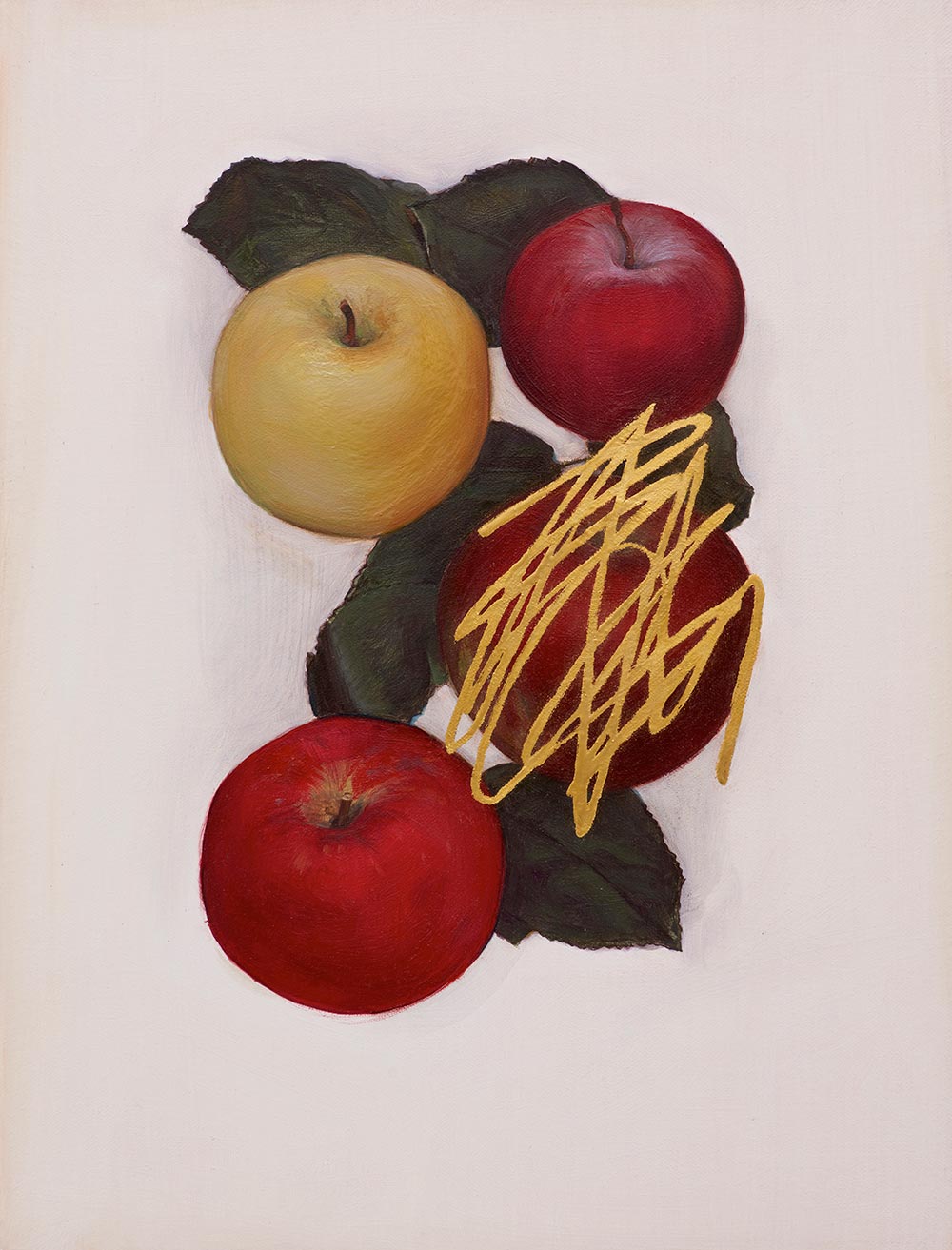

© Jen Mazza. Courtesy the artist and Tibor de Nagy Gallery, NY. Photography: Eric Wolfe

© Jen Mazza. Courtesy the artist and Tibor de Nagy Gallery, NY. Photography: Eric Wolfe

© Jen Mazza. Courtesy the artist and Tibor de Nagy Gallery, NY

Photography: Eric Wolfe

© Jen Mazza. Courtesy the artist and Tibor de Nagy Gallery, NY

Photography: Eric Wolfe

The retinal shudder/shutter: I am reminded of Anne Carson’s discussion of the etymology of the word cliché and the mechanism and sound that goes along with it. “Cliché is a French borrowing, past participle of the verb clicher, a term from printing meaning ‘to make a stereotype from a relief printing surface’. It has been assumed into English unchanged … partly because the word has imitative origins (it is supposed to mimic the sound of a printer’s die striking the metal) that make it untranslatable.”3

The work of art should not become readily translatable: i.e., the stereotype, the thing produced, but should be the machine from which ideas, clichés included, are generated. A painting should continue to make: it should be a system of signs of the convertible variety,4 that shift, not setting meaning through the instant aperture of the eye, but through a degree of ambiguity to engender multiple prospects, so that meaning forms and re-forms to develop alongside the motion of time.

1Pierre Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, (New York; London: Da Capo, 1987), p43.

2“We nearly always live though screens — a screened existence.” Francis Bacon’s words now seem to take on new dimensions. (David Sylvester, Interviews with Francis Bacon, (New York: Thames & Hudson, Inc., 1987), p82.

3Anne Carson, Nay Rather, (London: Sylph Editions, 2013), p4.

4David Joselit, “Signal Processing: Abstraction Then and Now,” (Artforum, Summer, 2011).

[Pollock’s] great accomplishment — and also the great accomplishment of Abstract Expressionist painting tout court — was to merge all these semiotic layers into a single convertible sign…

…[C]onvertible signs are what make Abstract Expressionist painting dynamic, open-ended, always in a process of becoming.

In every work of art there is an irreducible singularity; a fund of affect and visual event that is inexhaustible.

There is peace and security in Sign City. Thinking, there, is a matter of associating the right signs with the right things and then submitting these signs to the algorithm of your preferred ideology. But peace and security come at a price….

Dear Lorca … the tree you saw in Spain is a tree I could never have seen in California…’

I think this sense of painting being a temporal medium is one I also explore and I am very interested in the idea of “convertible signs” and what that may entail.