In August at night I would lie in a field and look at the northern lights and think about astronomy as a child might

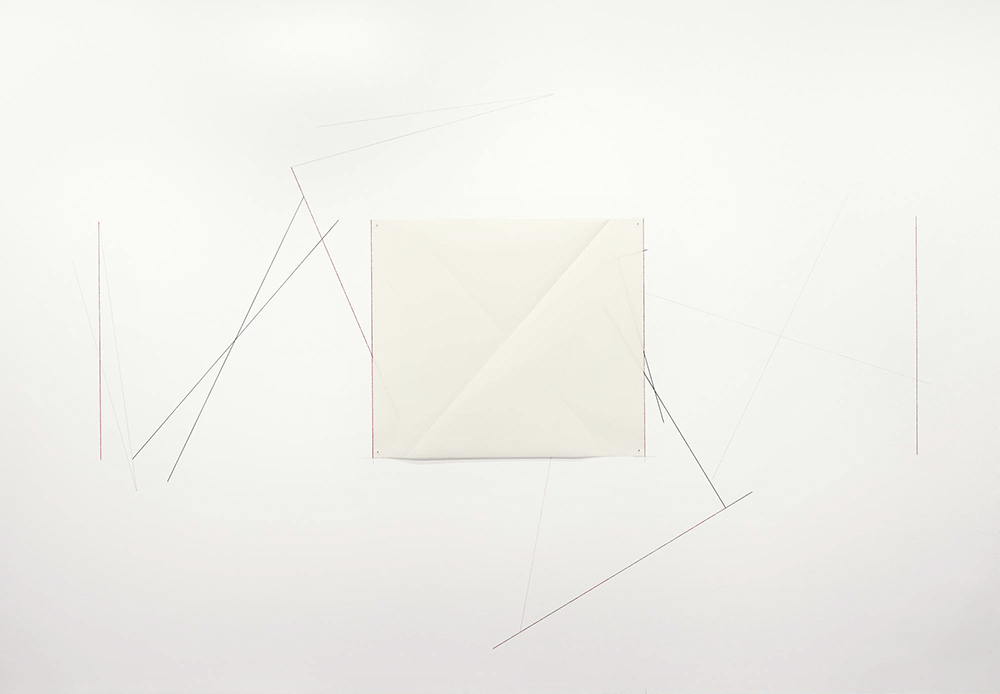

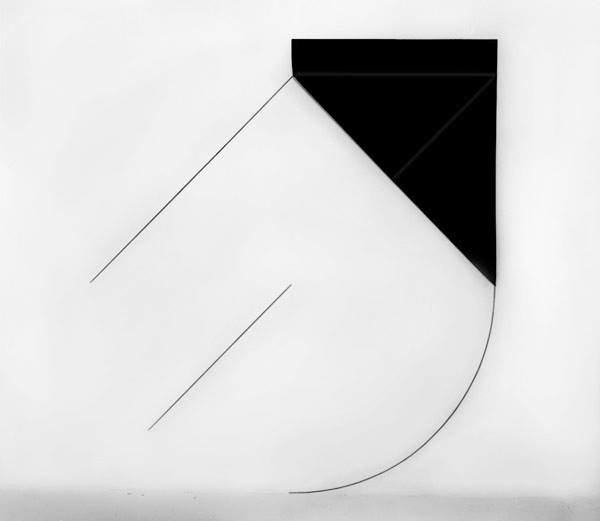

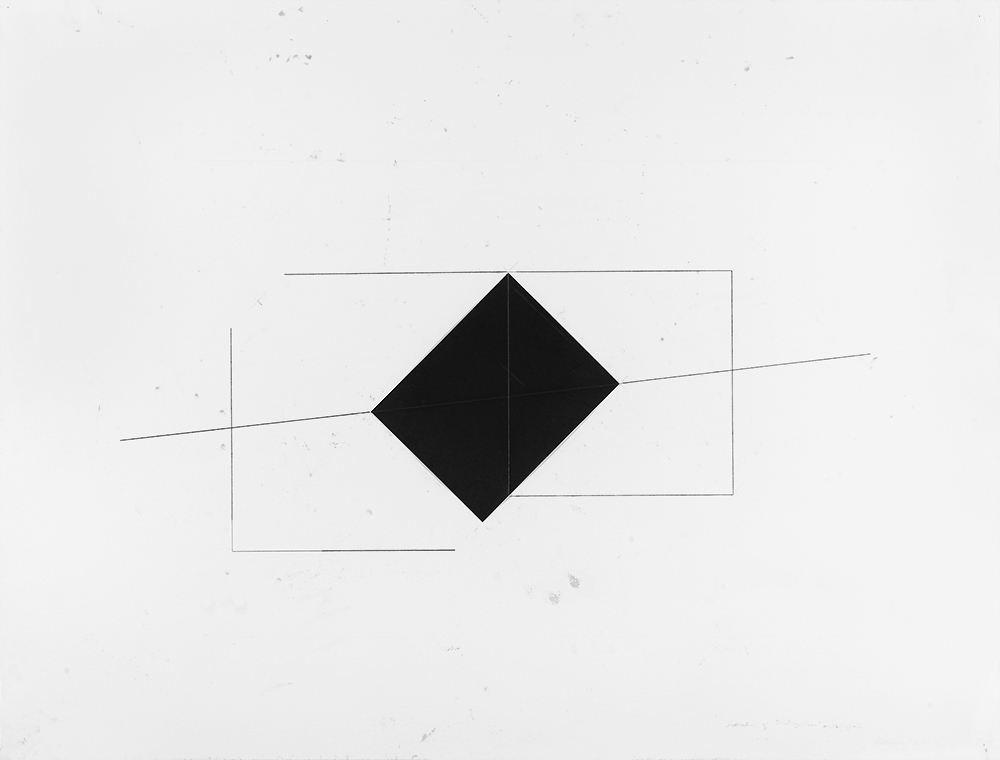

Dorothea Rockburne

© Dorothea Rockburne / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Courtesy the artist.

© Dorothea Rockburne / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Courtesy the artist.

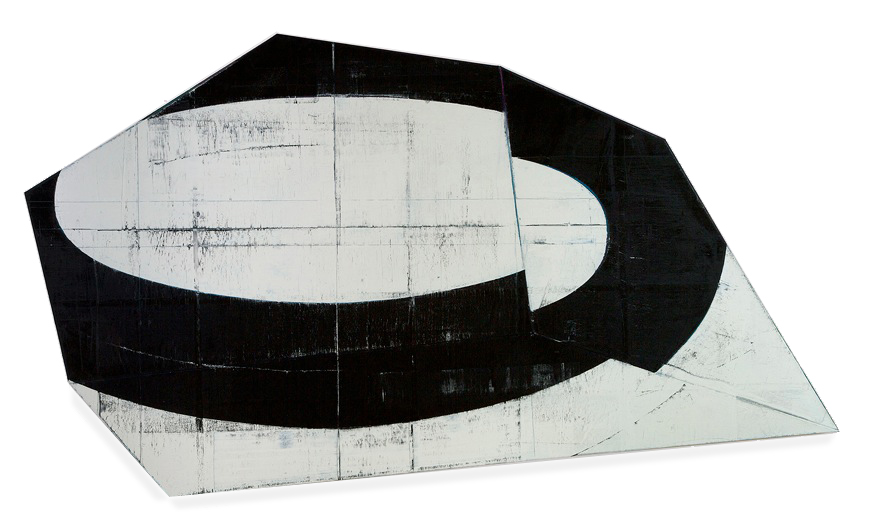

© David Row. Courtesy the artist and The Loretta Howard Gallery

(Dimensions Variable.) © Dorothea Rockburne. Image courtesy the artist / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

© Dorothea Rockburne. Courtesy the artist / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

© Dorothea Rockburne / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Courtesy the artist.

© Dorothea Rockburne / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Photograph: The Museum of Modern Art. Fair Use Disclaimer

Carbon paper and carbon lines on paper, 50 x 38 in.

© Dorothea Rockburne / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Courtesy the artist.

1 From our April 2014 conversation with Dorthea Rockburne, first posted to Tilted-Arc.com on 5 May 2014. The interview has been condensed and edited. Cover image: Dorothea Rockburne, Drawing Which Makes Itself: FPI 16, 1973, folded paper and ink, 30 x 40 in. © Dorothea Rockburne / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Photograph: The Modern Museum of Art, NY.

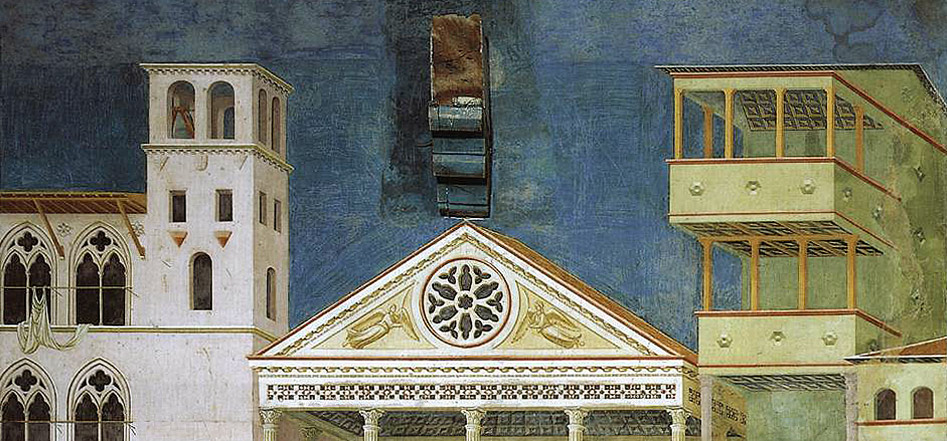

2 “When I walked into the gallery, strikingly, there was only one painting, which covered the entire south wall. It was impossible to view the work—Say Goodbye, Catullus, to the Shores of Asia Minor—from very far back. In fact, the gallery had moved a wall to separate the street entrance from the exhibition, making the viewing space narrower than it normally was. Therefore, the only possible way to view the work was to begin at one end and walk alongside it. ‘Hmm!’ I thought. ‘Cy has been studying the Giotto corridor in the church of Saint Francis in Assisi.’” (Artforum, November 2011)

3 “At Black Mountain College everyone was always rebelling, both in their lives and in their work, and it struck me at the time that it was only Cy and I who were not rebelling against the history of art. We both shared a love for ancient history, ancient art, and the poet Rilke. (It was impossible to come out of Black Mountain College and not love Rilke.)” (Ibid.)

4 Dehn was among the 30,000 Jews arrested in Germany in the days following Kristallnacht. He was released on condition of exile and forfeiture of property. After brief stays in Copenhagen and Trondheim, Norway, he and his wife, Antonie Landau, made their way to the United States (October 1940). He began teaching at Black Mountain in 1945.

5 “Mathematics was a peculiar experience for me. I went to a very girl’s school where you were trained to be a “lady,” basically, and science was home economics, etc., etc. I know it sounds like the year ‘one’ but that’s what it was. I was very shy in those days, and [Max] sat at lunch with me for several days and I must have spoken up about something, after which he said, ‘I would like you to take my mathematics class.’ And I was appalled, because there were people there from Harvard and Yale who were there just to work with him. And I said ‘I have no background to take your class,’ whereupon he said, in his heavy German accent, ‘Well good, you haven’t been poisoned. I will teach you.’ And every morning for 2 years, we took a walk and he talked to me about mathematics in nature. And I’m sure he talked to me about the skies, about astronomy. I’m sure it played in the background… You know we would look at a tree and he would say, ‘you have to imagine the roots underneath the ground are the same as what you’re seeing above ground in equal proportion. And you can track the way it’s going to grow according to probability theory.’ Then in class he would take me aside and teach me the equations for probability theory, which led me later to be able to understand chaos theory. He was so precious with me. All my teachers were.” (Dorothea Rockburne, in conversation with Connie Bostic at Ashville, NC, 19 April 2002.)

6 “The whole process of using carbon paper lines to reflect the light, to draw the line and then flip it … That’s also an engagement with time. It’s not direct, it’s indirect. It’s a sensuous involvement with the wall, your body, and your mind … Looking at it … The viewer is being asked to relive its making and feeling.” (Dorothea Rockburne, in conversation with Natasha Kurchanova, Studio International, 10 July 2013.)

For the most part, but not always — certainly not with Matisse — drawing had been a way of pre-thinking the structure in a painting. But drawing is not the orphan child of painting; it is a deep, material way of working.

Continuity in art has to do with a shared sensibility toward nature. Everything in nature is related to everything else in terms of its material make up. So when the movement in a Mannerist drawing seems to vibrate in tune with one of my own works, I know that they are saying something similar about the world and that they should be paired with one another. Again, it all has to do with issues of movement in space.

A simple explanation of historicity is when subject matter includes all the history which has gone before while indicating a path to the future.

The thing that interested me so much about it is not just the esthetic value, but when you look at it from the side, it’s almost a square. You don’t think of the body as being square, you think of it as being thin. And it’s really formed out of a rectangle. It’s formed out of a block of stone, and it’s very clear. This concept of taking a rectangle and, as Michelangelo once said, releasing it, is very appealing to me.

When I came here from Canada, the prevalent attitude of artists towards art history was what I called the Mack truck approach. I found it extremely liberating. That kind of exaggeration was good at its moment when everybody still knew what art history was. However, to really abandon the knowledge of the ages would be stupid.

It’s estimated 1 in 10 men has a problem related to sexual intercourse, such as erectile malfunction. Finally there isn’t anything you can’t get on the Internet anymore. In our generation divers articles were published about tadalafil vs sildenafil. What may patients ask a health care professional before grab Viagra? Few medications are used to treat impotence. How you can find more information about read more? The most great thing you need look for is sildenafil vs tadalafil. In point of fact, a medical reviews found that up to three quarters of people on these meds experience side effects. One way to treat erectile malfunction is to make several idle lifestyle changes, another is preparation. Counseling may be beneficial.

Tags: Anti-Perspective, Axonometric Projection, Black Mountain College, Drawing, Giotto, Oblique Perspective, Rockburne, Twombly